Semillera

Pamela Arce

19 May–5 Jun 2021

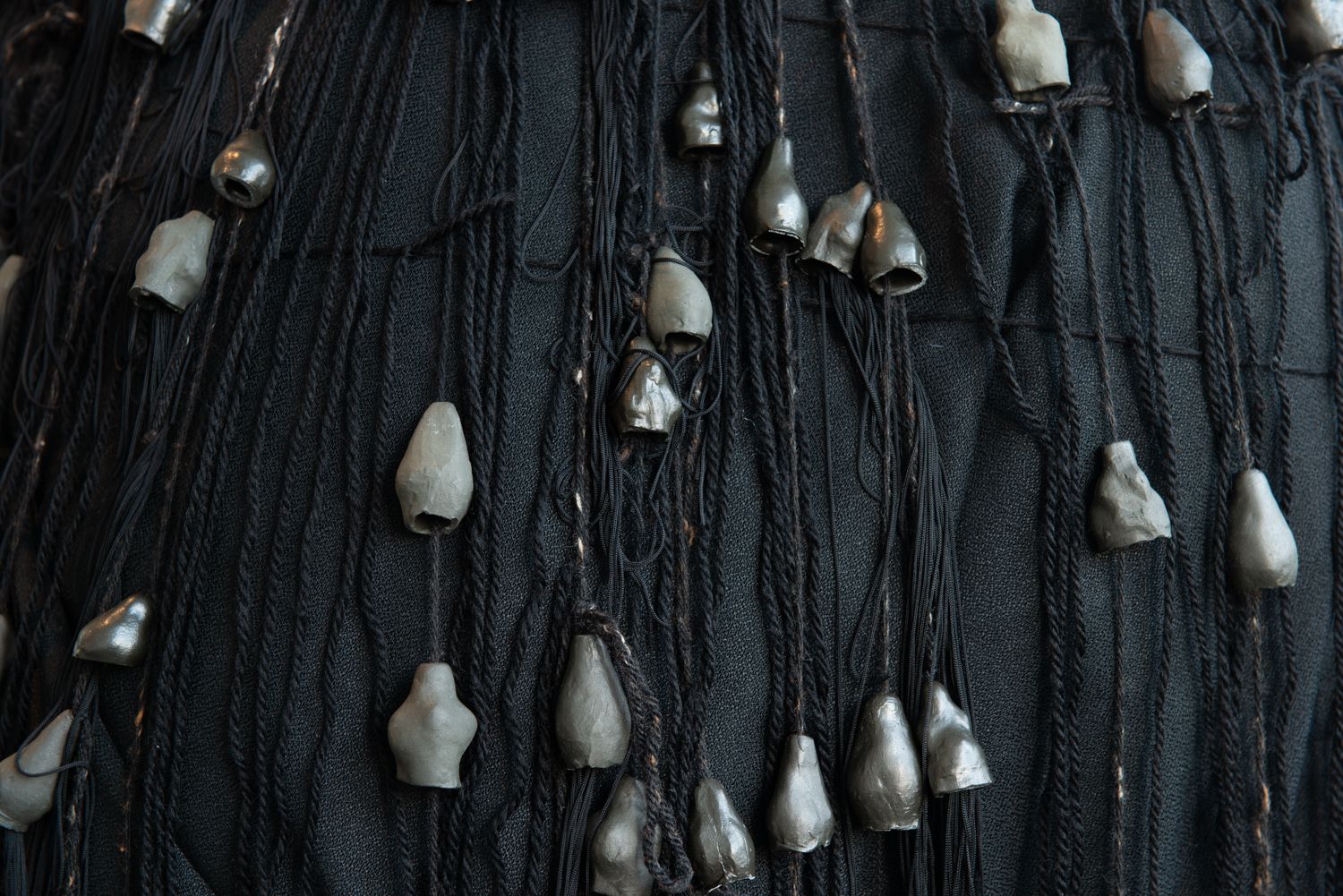

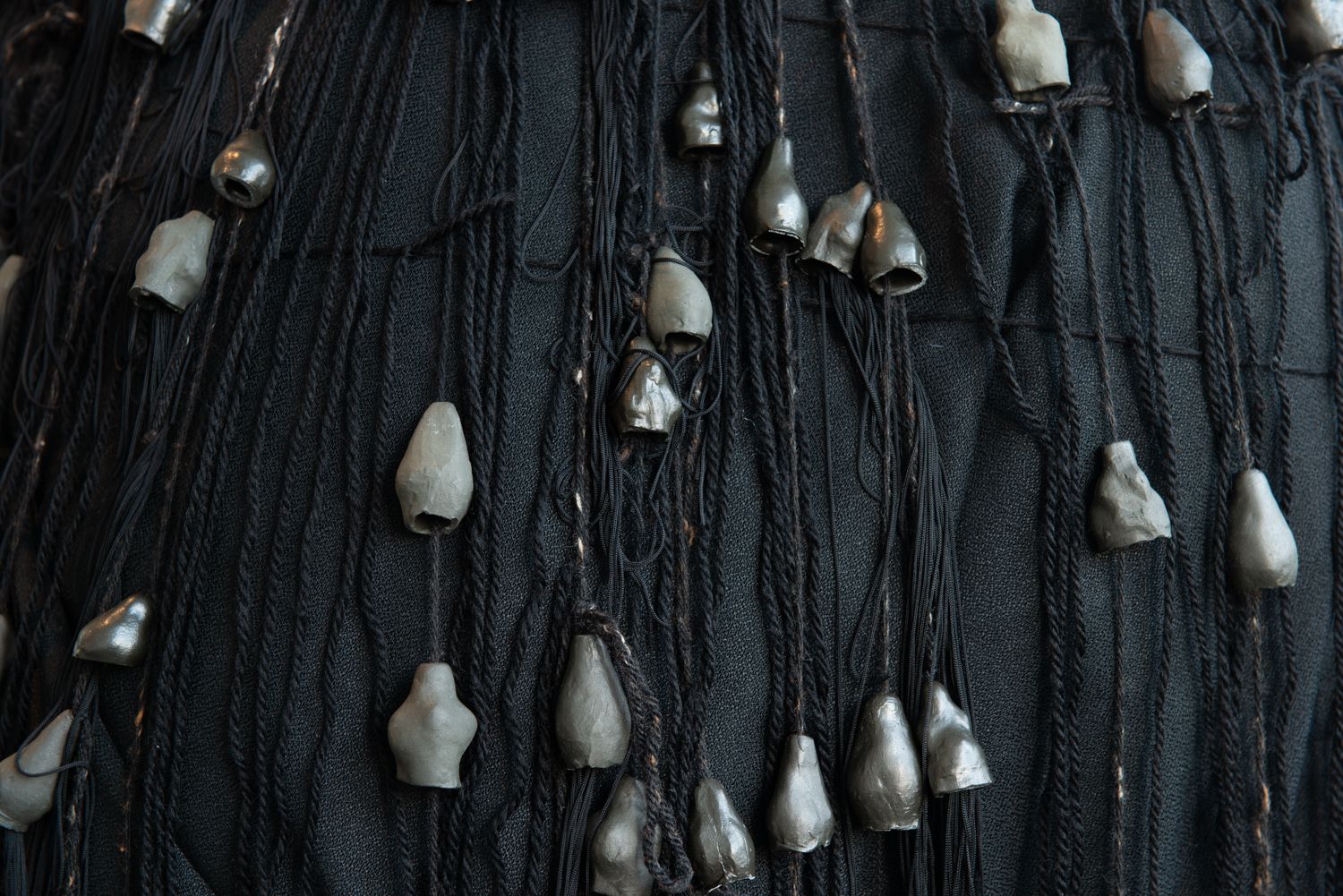

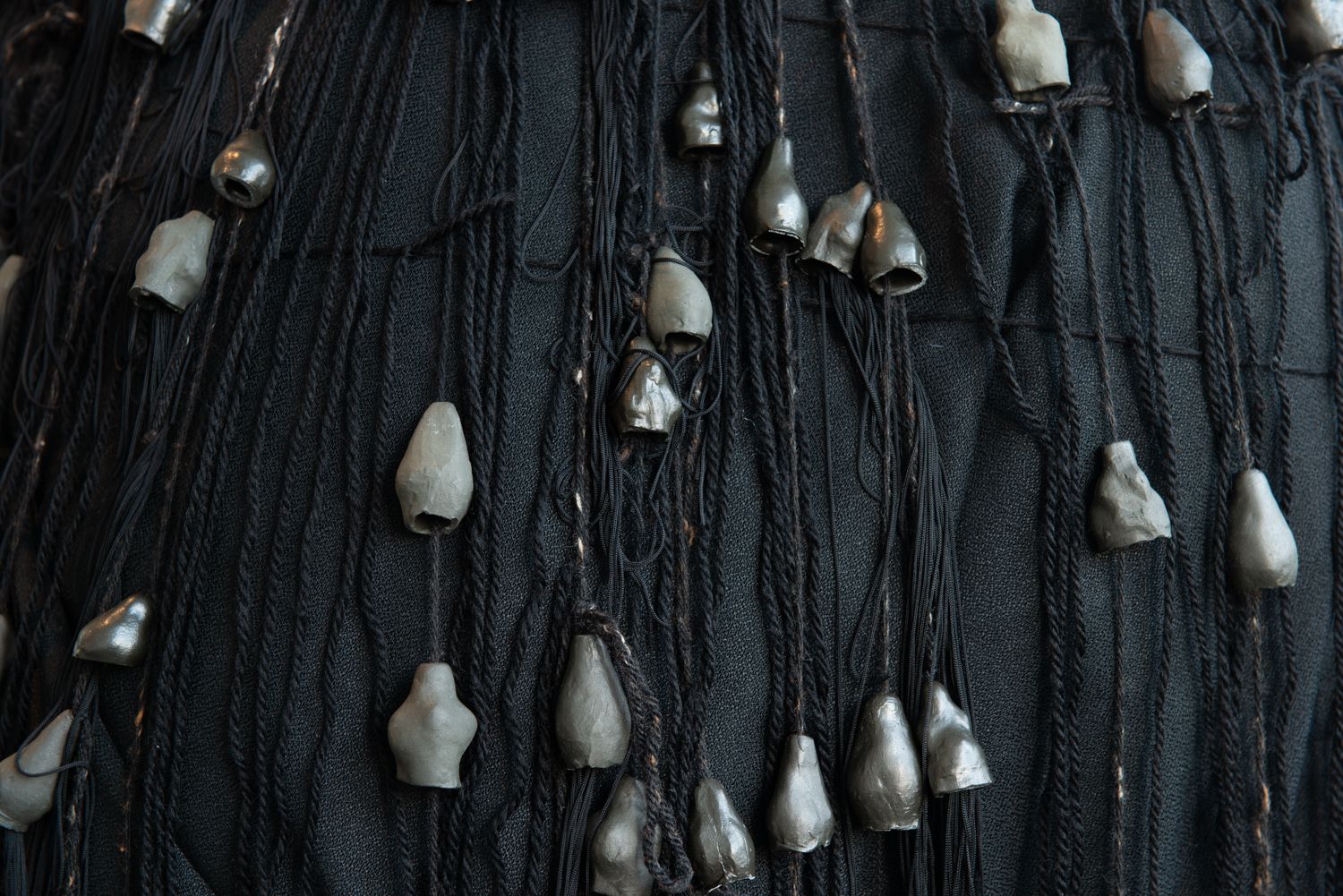

It’s been two years of devastating death, of people and also of the world as we know it. An apt Andean concept for this time is Pachakuti - the turning upside down of the world. Bolivian theorist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (2020) urges us to befriend death. Pamela’s fardos funerarios with all their threaded care and attention to detail are not only reminders of death-as-we-know-it. Covered in burnt activated seeds, the fardos somehow turn into “semilleros” (carriers of seeds), sonajas cantarinas. And the tapestries of woven little mouths crafted in black clay also sing songs of affirmative transformation.

Semillera befriending death in the Pachakuti

Sarita Gálvez

A year after Pamela shared her first fardos funerarios in Jaggera Country (Meanjin/Brisbane) as an exercise of memory and more-than-human responsibility after the catastrophic summer bushfires that took the lives of nearly 3 billion of non-human animals, she decided to bring them back to Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung Countries, to continue to honour and remember the teachings, losses and darkness of death. A process that has been intensified by the global Covid-19 pandemia, in a world already suffering the careless force of advanced capitalism and environmental degradation.

The origin of the fardos funerarios goes back to thousands of years ago in the Andes. They are part of the complex burial practices of the ancient Paracas culture, where bodies were covered in layers of intricate textiles designed to weave and facilitate the passage of the spirit into the other world.

In this second iteration of Pamela’s work with the fardos funerarios, “Semillera” the semillas (seeds) are those who help us to connect the burnt trees and activated seeds of the Amazon and Australian bushfires which originated by a deadly mix of climate change, colonial land management and corporative greed. With the sudden necessity most of us felt during covid-19 lockdowns for cultivating our food in times of scarcity and strict borders restrictions. With the precarious life of native seeds in times of genetic manipulation by greedy corporations such as transnational Monsanto. As the Kichwa leader Patricia Gualinga puts it “El extractivismo no está en cuarentena” (extractivism doesn’t go into lockdown).

It’s been two years of devastating death, of people and also of the world as we know it. An apt Andean concept for this time is Pachakuti - the turning upside down of the world. Bolivian theorist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (2020) urges us to befriend death, a practice that’s been so constantly avoided by Western and Westernised societies, where death is continuously swept under the carpet in a Capitalistic driven desire to carry on with “the new normal” or a “post-Covid” life. Yet not the whole world is in a privileged “post” position. Certainly not Pamela’s homelands. More people are today dying in the lands of Abya Yala than last year. And while Australia can rest in its effective management of Covid-19, less action has been taken to address the continuous death in custody of Aboriginal people after 30 years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

Pamela’s fardos funerarios with all their threaded care and attention to detail are not only reminders of death-as-we-know-it. Covered in burnt activated seeds, the fardos somehow turn into “semilleros” (carriers of seeds), sonajas cantarinas. And the tapestries of woven little mouths crafted in black clay also sing songs of affirmative transformation. Perhaps these sounds and songs will remind us of some of the teachings of the tiny little virus that inundated the world’s lungs: yes, the world CAN be completely different. Others forms of relating are possible, hyperlocal networks of care and food sovereignty are vital in urban environments, basic income should be a norm, homeschooling and unschooling are viable and joyful alternatives for our young people and their older companions, and we can not forget that what’s actually creating this massive wave of death in the world is not the virus but the force of advanced cognitive capitalism and its deeply unjust and racist apparatuses of labour, health and education. That’s the real global pandemics, one that continues to bleed heavily in Abya Yala since colonisation: Nuestra tierra triste.

So, the question prevails, here today with our bodies breathing air on stolen Aboriginal Land. How not to forget and resist surrendering to the seductive Capitalistic force of sudden comfort and continue to carry-on a post-Covid life?

I wonder if by staying a bit longer with death, befriending la muerte, listening to her seed songs we might attune to other ways of becoming lively with the Pachakuti?

References

Rivera Cusicanqui, S (2020) “Resistencia, insurgencia y lucha en tiempos de exterminio” in “Sentipensarnos Tierra: Epistemicidio y genocidio en tiempos de Covid-19”. 1st Edition. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Gualinga, P (2020) “El extractivismo no está en cuarentena” in “Sentipensarnos Tierra: Epistemicidio y genocidio en tiempos de Covid-19”. 1st Edition. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

It’s been two years of devastating death, of people and also of the world as we know it.

Pamela Arce explores our understandings about multispecies relationships and the interdependence and mutualism that animate our relational multiverse through her work with ceramics, textiles, and video. Based on the effects that patriarchal reason, since prehistoric times, has had in organising these relationships and shaping contemporary Western ways of feeling, her work addresses the history of extractivism as one of the expressions of the patriarchal heritage extended in the current forms of ecological and civilisational crisis. The stories she transmits act as passageways to territories, in which thinking and feeling are woven.

Most recently, Pamela undertook the Encuentro Hawapi Máxima Acuña and Villa Lena Foundation residencies (Perú and Italy), exhibited at Outer Space (Brisbane) and in 2020 was awarded a Gasworks (London) residency to be completed (when possible) in the coming months.