sonic.land

Reuben Derrick, Edwina Stevens, Rachel Shearer, Clinton Watkins

2–19 Sep 2020

SONIC.LAND shares new artwork by Rachel Shearer, Clinton Watkins, Edwina Stevens and Reuben Derrick, four artists from Aotearoa – New Zealand who work with environmental sound.

This is a project which rejects staid models for environmental listening and recording in favour of pluralistic, subjective encounters. Attendance, spontaneity, reflection and deep engagement with the environment are presented and celebrated as ends in themselves, as well as modalities for developing meaning and understanding in relation to the world around us.

Through a presentation of sonic artworks and a series of long-from interviews between the artists and curator, sonic.land explores the individual strategies and thought processes of leading NZ sound artists as they relate to environmental recording and associated practices in Aotearoa – New Zealand.

Access sound recordings and long-form artist interviews online

NOTES ON THE FIELD

An argument could be made for field recording being the art form most intimately concerned with the world around us. Both in its intent and means of execution, field recording is unthinkable without the multifaceted soundscapes the world produces and contains. The constantly evolving global soundscape offers recordists an essentially unlimited field in which to work, however, in many respects the most potent value of this practice has less to do with the recording, documenting and (re)contextualizing of a series of events over a particular passage of time, and is more significantly related to the potential for deep engagement – first at the level of physical presence and curious attention, and then, subsequently, at the level of concept, thought and reflection – which the practice of field recording offers those who are ready to listen with an open ear. It follows that field recording is at its most penetrating when practiced not as an ethnographic, anthropological or biological tool, but as an artistic or musical action, in which its quality and potential is limited only by the collected imaginations and interests of those who enact it.

With this in mind, the purpose of this text (or indeed this project as a whole) is not so much to mark out a border around what artistic or musical field recording is or isn't, or to suggest what it could or should be. Nor is it to assert that a given manner or motivation for working artistically with the sounds of the world is better than any other. Rather, the hope is that through this exploration of work by a group of artists who I admire, the variety of their practices might serve to inspire others, if not to pick up a recording device themselves, then to at least listen a little more intently to the soundscape surrounding them.

At first glance, it may seem that the primary concern of the field recordist is similar to that of a landscape painter and nature photographer whose purpose is to record or celebrate the world as it appears to them. In travelling to a location of interest, parallels can readily be drawn between the recordist and the painter romantically perched in a field with their easel, or, as they adjust the gain of a microphone, with the nature photographer setting the aperture of their lens and framing up a shot. While these comparisons are in some ways apt, I would propose that, as is true of successful work in other fields, what is most significant in the best examples of field recording often relates to ideas which go beyond that which serves as a work's material. In the works collected here we find the artists considering many different ideas concerning composition, perspective, place, and energy exchange, and while these explorations take place against a recognisable backdrop of the study and artistic reproduction of a place, their remit extends far beyond a physical location.

The work of a field recordist takes place in two breaths, inward and outward, collecting and presenting, and in two scenarios, the field and the studio. Their attention is Janus-like, directed at the world to which they listen intently, and to the sounds of the immediate or distant past – already recorded; held in digital or actual memory – and how these may compliment what is occurring in the present. While in the process of making a recording, the artist is often occupied by conceptual and aesthetic criteria which goes beyond mere interest and informed by a commitment to the idea of the now – time passes once, therefore there are no second takes, only additional recordings. This necessarily includes an openness to the unexpected, which sometimes extends to an acceptance that, if an 'error' occurred, then it took place, and should therefore be retained in honour of that past procession of presents. In the field, the recordist is also a collaborator, working amidst the soundscape as an active partner equally essential to recording. While attending to sounds of the present moment, the recordist may also be considering what contextualizes that which they are hearing, their decisions and movements informed by ideas of sonic combination and a knowledge of what they have, and of how each moment in the present builds toward the work as whole. [1]

If time spent in the field is typified by an artist's collaboration with the soundscape, it is upon entering the studio that their individual intentions are able to move toward the centre of their focus. Once in the studio, the sounds of the world become malleable, a material to be manipulated to the ends of the artist just as a sculptor might work clay. The degree of this manipulation exists on a spectrum extending from the subtle to the transformational, while in some cases a commitment to the genuineness of the recorded moment prohibits editing entirely. This is not to suggest that the process of recording itself is not creative. The choice, placement and calibration of the microphone(s), the movement of the recordist, the decision of when to end the session, all play a part in what can only be considered a creative activity. However, the studio affords an artist a degree of control precluded in the act of recording where the elements determine the manner in which the recording can take place. Once a recording has been made, an artist can work at their leisure. As opposed to a sound in the world which may be fleeting, a recording can be kept for years during which its source may be forgotten entirely as, over time and through manipulation, it becomes unrecognizable.

Through the commissioning of new artworks and a parallel series of long-form interviews, the aim of this project has been to communicate the motivations, interests and methodologies of four admirable artists, articulating the development and conceptual foundation of their work in all its detail and difference. By exploring the foundations of these works and the individual interests and perspectives the works are predicated on, it is my hope that a multifaceted picture can emerge in which field recording as a discipline – a field of practice – can be evaluated in a variety of cogent and relevant modes. Beyond this, I also hope that what emerges will relate, subtly or overtly, to some of the geographic, ecological and cultural specificities of Aotearoa – New Zealand; that through the works collected here and thoughts of those who made them, we may infer something about the place where the works were made, which – with field recording being, as it is, intrinsically related to the places it occurs – informs the selected artists in their life and work.

While they are united in their use of recorded sounds of the world as a principal material, the artists here are motivated by distinct and uniquely individual interests and curiosities, and carry out their projects in ways – employing collage, involving collaboration, sonification, or audio-visual recording, with planning or spontaneously – which further serve this differentiation. Throughout this project I have endeavoured to avoid a prescriptive tone; the purpose here was not to argue that certain ways of thinking or working are better or best, or that some thoughts and opinions are authoritative. If an overarching through-line or didactic theme is unavoidably assumed, let it be that environmental sound recording has been positioned as a fertile and meaningful means of creative exchange with the surrounding environment, and that the situation of such exchanges is best approached with an openness for the unexpected and a respectful curiosity for that which surrounds us.

– Sam Longmore

1. I am wary of anthropomorphizing the environment. However the conception of a soundscape as collaborator is possible without undue attribution of human motivation, characteristics, or behaviour to inanimate objects, animals, or natural phenomena, and it is simply a question of accepting the capacity for agency in non-human entities – a lesson of respect for things beyond us which we would do well to learn soon.

This project was conceived in 2019 and was intended to feature as part of the 2020 exhibition programme at BLINDSIDE, Naarm – Melbourne. It has been developed as an online project with support from the Audio Foundation, Tāmaki Makaurau – Auckland, whose International Presentations programme is generously supported by Creative New Zealand.

SONIC.LAND shares new artwork by Rachel Shearer, Clinton Watkins, Edwina Stevens and Reuben Derrick, four artists from Aotearoa – New Zealand who work with environmental sound.

This program takes place on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. We recognise that sovereignty was never ceded - this land is stolen land. We pay respects to Wurundjeri Elders, past, present and emerging, to the Elders from other communities and to any other Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders who might encounter or participate in the program.

Reuben Derrick is a sonic artist and composer active in New Zealand and Australian exploratory music communities. Reuben’s Doctor of Musical Arts research ‘Acoustic illuminations: recorded space as soundscape composition’ (University of Canterbury 2014) drew upon field recordings and improvisation in order to explore ways performers might engage with sonic environments. As a performer, Reuben works solo and in groups in exploratory and improvisational contexts. His compositions include works for jazz orchestra, small ensembles and improvisational groups as well as electroacoustic works which focus on environmental sound. Reuben performed throughout Central Europe (2019), The Nowhere Festival (Auckland, 2018), the Radio Asia Festival (Warsaw, 2018) and at the Music Matters Festival (Colombo, 2016). He was awarded a fellowship to the Music Omi residency (New York, 2015).

He is a member of the Cantabrian Society of Sonic Artists for which he hosts visiting artists and facilitates experimental music events. Sam Longmore is an artist, electronic music and writer based in Auckland. His work is informed by the relationships between geography and acoustics, soundscape and phenomenology, installation and architecture.

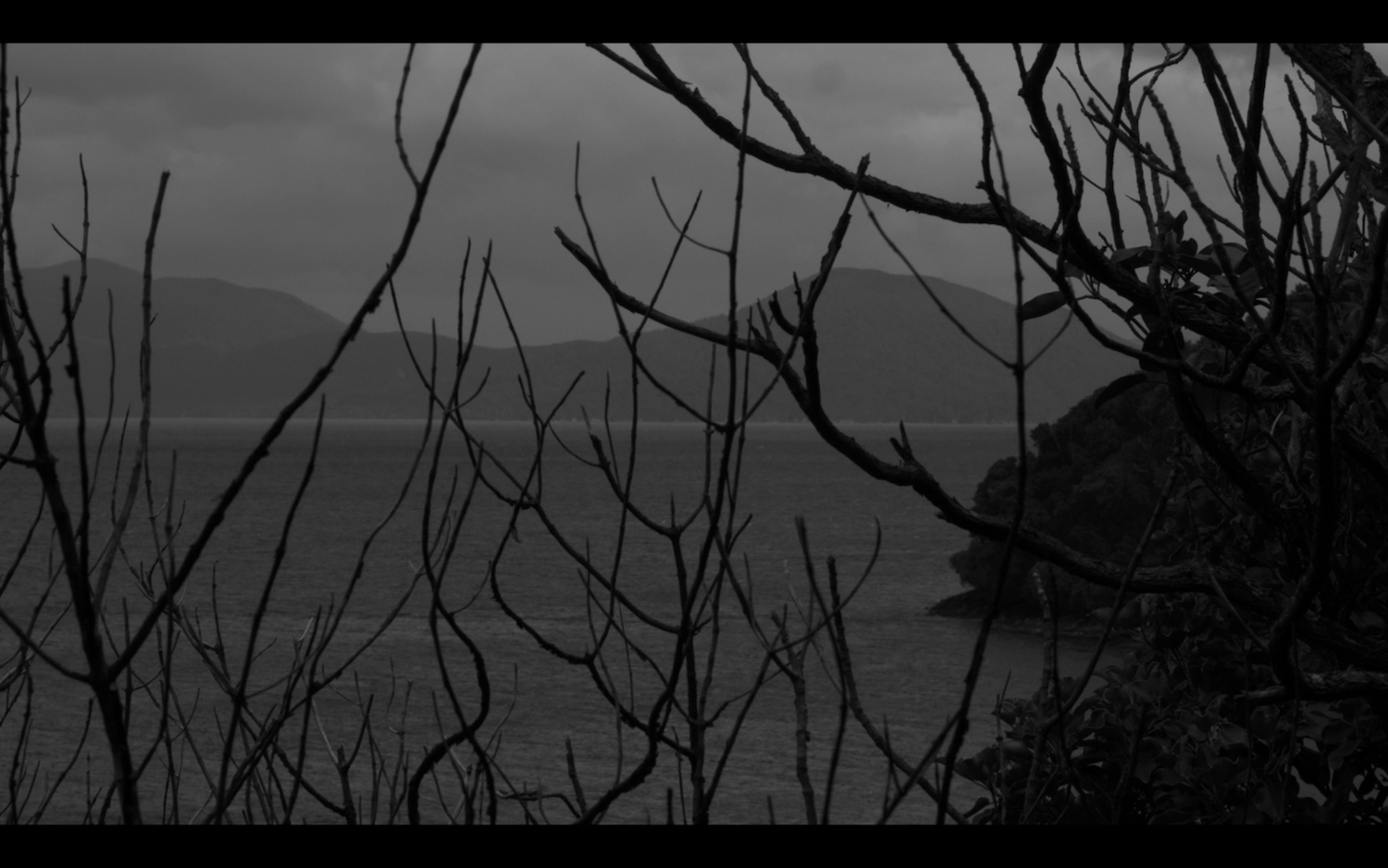

Edwina Stevens (Ede Eves) is an audiovisual artist working across live performance, installation and spatial sound design, whose work investigates the 'sound of place' via composition, improvisation and performance. Working with analogue audio equipment, found acoustic instruments, as well as field recording equipment such as a DSLR camera and portable audio recorders, her minimal and haunting soundscapes specifically relate to experiences of remoteness, where time behaves differently, occasionally induced further by minimal cinematic imagery. A substantial amount of Edwina’s work has been produced during self-directed residencies and impromptu travel.

Rachel Shearer works across a range of fields – experimental music, installation, academic research, audio visual projects and collaborations with practitioners of moving image and performance. She holds a practice-led Phd which investigated earth-energies and environmental recording through a lens of Maori epistemologies.

Clinton Watkins works across audio visual installation and experimental music. He has been producing, exhibiting and performing his work for over 20 years throughout New Zealand, Australia, Europe, Asia and the United States. Most recently, Clinton has been working as the sound designer and composer as part of the artist collective, Field Recordings and was a participant of the Sonic Mmabolela 2018 sound composers residency directed by Francisco Lopez. Clinton has a Doctorate in Fine Arts and is a lecturer at Auckland University of Technology specializing in sound.

Sam Longmore has been employed at The Audio Foundation since 2016. He completed a MFA at the Elam School of Fine Arts between 2014 – 2016, during which time he twice received the Paul Beadle post-graduate research scholarship. He has performed and exhibited at galleries and project spaces throughout Aotearoa and abroad, and contributed writing to several institutions and journals, notably a piece for Artspace about Julian Priest’s 2014 Chartwell commission, La Scala, and to the Goethe-Institut Neuseeland’s Themendossier around Hanno Leichtmann’s 2018 artist residency. In addition, he runs the mf/mp imprint with Wellington-based artist and musician Karl Leisky.

Related

1 Aug–30 Oct 2020

the place one lives.,

Talia Smith, Leyla Stevens, Miko Revereza, Amrita Hepi

17 Mar–3 Apr 2021

No Comment

Bridget Chappell