Stardust

Kirsty Macafee

23 Jan–9 Feb 2019

My interest in this image responded to the idea that “the status of being everywhere at once is what now produces value for and through images”.

The reverse processing and reformatting of the image data can be described as a continual and unfolding process of construction, deconstruction and re-construction. Imagery and image data were utilised as material, printed onto an unfixed support. This process was considered as representative of the way images inhabit multiple states, sites, and spaces at one time, are endlessly malleable and continually reinvented. The project was an exploration of the constantly in flux condition of both images and identity and considers the unstable truth of images, and of being.

Made with Alex Macafee.

Command+Shift+3: Print screen

One Saturday in January 1973 Brian Duffy clicked the shutter on his Hasselblad to capture David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust. The Ektachrome negative registered Bowie’s gently closed eyes, and the oily sheen of a lightning bolt emblazoned across his face in red-lipstick. The picture would become the cover for Bowie’s sixth studio album Aladdin Sane, a release he once described as “Ziggy goes to America.”[i]

On news of Bowie’s death, forty-three years later, copies of Duffy’s photograph flooded social media. By then its emulsion surface had been transformed into a stream of ones and zeros. Uploaded, copied, compressed and remixed, the picture was liberated from the hallowed halls of music fame and thrust into digital ubiquity. Today if you search “iconic album” Google delivers thumbnails of Aladdin Sane in 0.58 seconds.

Like many of us online the day that Bowie died, artist Kirsty Macafee was inundated with repeated flashes of Ziggy’s face. Buffeted by a giddying sea of images she pressed Command+Shift+3 to capture a screenshot of the Aladdin Sane cover. For a moment, the ceaseless stream of data paused. And a second, third or even fourth generation PNG was archived.

The exhibition Stardust uses Kirsty’s screenshot as its point of departure, and in this way joins a collective urge to rip and share celebrated images. But her actions differ from the parodies and tributes that typically populate the internet. Instead of re-presenting the original photo—through, for example, appropriating or re-enacting its content—Kirsty has reduced, re-assembled and dissolved the image data itself. Her actions mirror the life of photographs as they circulate in our digitally networked culture.

Stardust takes as its subject our world in which photographs are both abundant and depleted, using an image of Ziggy Stardust as an exemplar. The Aladdin Sane photograph has become a poor image, to use Hito Steyerl’s phrase, that is “compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.” [ii] The photo has been edited and shared countless times; appropriated for Harry Potter spoof albums and re-enacted by Lady Gaga and Kate Moss to sell music and magazines. Users have become the editors, historians, and authors of reproductions, using the original shot as a template for their efforts. This is a digital photograph that has turned into its own negative, shedding pixels and even punctum[iii] as it self-replicates.

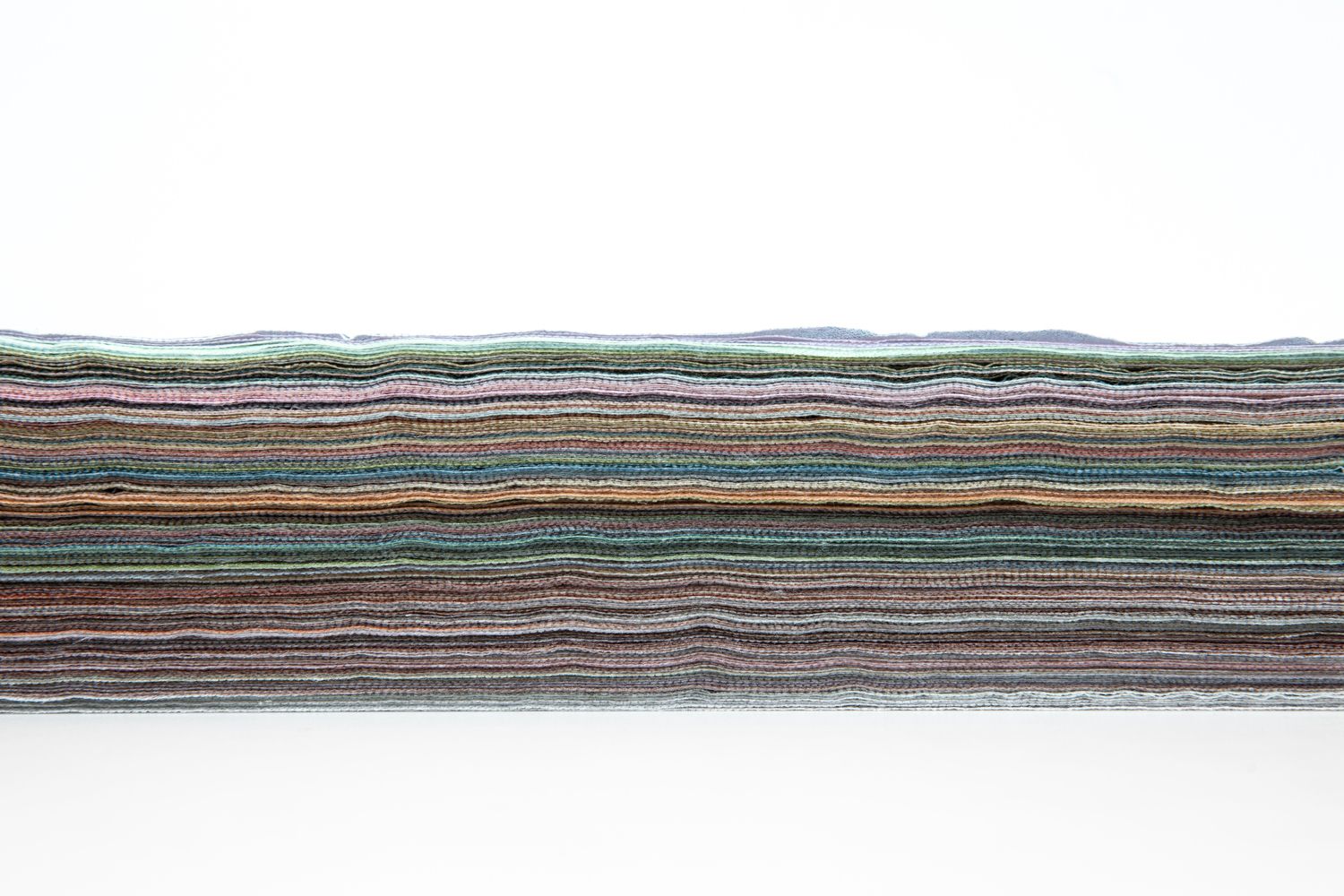

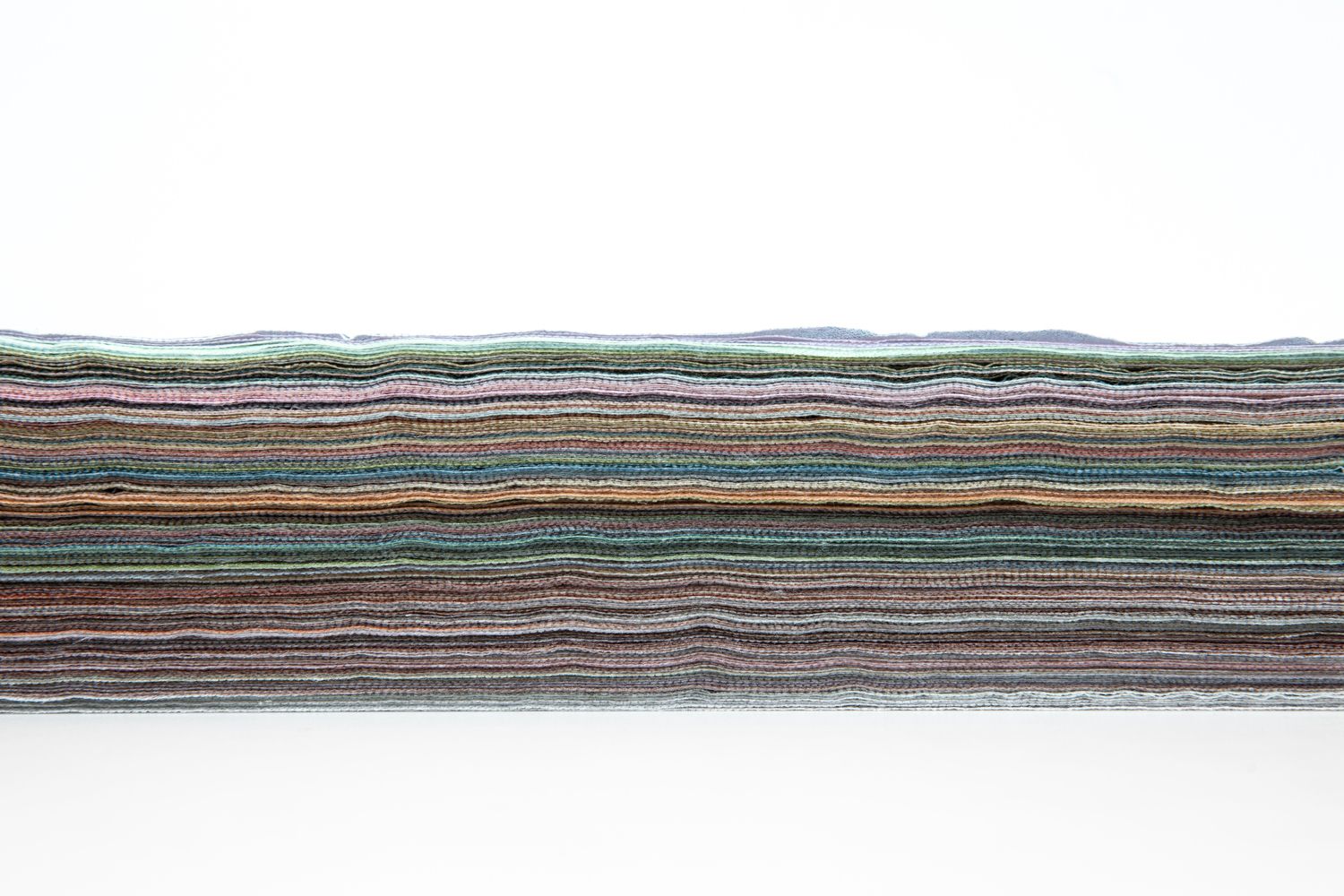

In Stardust, Duffy’s photograph—or more accurately, a screenshot with unknown degrees of separation to Duffy’s photograph—is reduced even further to simple blocks of colour. It is reformed into a gridded network of pinks and olive greens, evoking the placeholder colours used for so-called ‘lazy loading’ images.[iv] The grid extends from wall-to-wall, as if Kirsty has willed the image to return through the simple act of repetition.[v]

But if Stardust attempts to restore an image, the attempt has been thwarted. In a further act of reduction the printed bricks of mauve, coral and dusty blue have been dissolved directly onto the gallery wall. Once immersed in water the ink substrate has liquefied, leaving behind a delicate skin that evokes the “soft, wet, labile membrane”[vi] of photographic emulsion.

It is in resurrecting the tactile surface of photographic paper that Stardust also offers up a picture of photography’s dissolution. There is, in fact, no original image (or even depleted copy) to be found in the gallery. The photo ‘as picture’ is absent. What remains is evidence of the cycles of storage, reformatting and loss that characterise photography today. Stardust denies us ‘the photograph’, and instead embodies the conditions of circulation through which our pictures both disintegrate, and cohere, in the digital age.

Dr Clare Humphries

Artist and Visiting Lecturer at the Royal College of Art, London

References

[i] David Buckely, (1999). Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Publishing, p.157.

[ii] Hito Steryl, (2009) ‘In Defence of the Poor Image’, in e-flux journal, issue 10, available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/

[iii] Roland Barthes famously defined the punctum as a kind of wound, or the intensely subjective force of a photograph. If there is a wound in Duffy’s photograph, it is healed in re-enactments by parody and proliferation, although it may arguably be recuperated in a new form through multiplication. Roland Barthes (1993; first published 1979). Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. London: Vintage.

[iv] Software developers can maximise web-page performance by delaying the loading of images, and providing a temporary placeholder instead; this can include choosing one dominant, or vibrant HMTL colour in the file to keep space for the image.

[v] A second work in the Stardust exhibition, Deep Time, the blocks of colour are pushed all over again, over-printed one-on-top-of-another 256 times, in what seems a further attempt to bind the photograph together once more.

[vi] Martyn Jolly, (2002) ‘Faces of the Living Dead’ in Photofile, 66, p. 38.

Colour information extracted from a screenshot made on 10 January 2016, archived, subsequently reworked and flooded onto the gallery wall.

This program takes place on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. We recognise that sovereignty was never ceded - this land is stolen land. We pay respects to Wurundjeri Elders, past, present and emerging, to the Elders from other communities and to any other Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders who might encounter or participate in the program.

Kirsty Macafee is a Melbourne-based artist working with images across digital and analogue technologies. Her practice is multi-disciplinary and process based, It is informed by an expanded and deconstructed view of photographic practice and engaged in post-photographic and feminist discourses.

Related

18 Sep–5 Oct 2019

Plexus

Will Cooke, Annelies Jahn, Ham Darroch, Lieutenant + Vassallo, Nadia Odlum, Katy Mutton, Britt Salt

23 Jan–9 Feb 2019

Live Work

Arini Byng, Aaron Christopher Rees

6–23 Mar 2019

I thought you’d never ask

Tess Landells