Siying Zhou in conversation with Youjia Lu

Siying Zhou

Identity. Video art. The gap.

While making work for the Blindside exhibition George prefers Forks, I read Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism. In this book, Anne offers a perspective with which to approach and understand the unique race and gender category of ‘yellow woman’. She believes that through this inseparable association with object hood (drawn from the technologies of embroidery, ceramic, robots and food-making), East Asian women can develop their own ground in the intersectional discourse about race and gender, and articulate a different kind of surviving history in Western society. In the beginning of Ornamentalism, Anne reveals that the critical race and gender examination of ‘yellow women’ is insufficient, and still tends to follow the theoretical frame that was created in the 70’s. She underlines the fact that we still know very little about East Asian women while the race and gender of ‘black and brown’ women has been constantly examined and studied along with the social changes in the Western world.

When I read Anne’s argument, I recalled a moment when a female curator who has Asian cultural heritage casually revealed to me that she was sick of the topic of the Asian female body in the arts, implying that this subject was overly explored and had became monotonous. My question is: how could we be sick of something that we know so little about? As Anne draws her evidence from American history and mainstream culture, I wonder how Ornamentalism is applied in the Australian social and geopolitical context. Could Ornamentalism provide a place for East Asian women in Australia to grasp their existence? More importantly, how does the Ornamentalist perspective reshape the quintessential tradition in Western Art of examining the materiality of artistic media and insert racial and gender context into such an examination?

While I was contemplating these answers through the process of manipulating images and objects, my research into the Australian past and my examination of the sartorial relationships that a Chinese woman could draw, I spoke with four Melbourne/Naarm-based Asian female artists and asked them how they navigate their racial and gender identities through their studio practices.

This is the edited transcript of a face-to-face conversation taken between Youjia Lu and Siying Zhou in February 2021. This conversation took place on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation.

Siying Zhou (SZ): How are we going to start this conversation? How do you identify yourself? In the current socio-political climate, identity becomes so essential for artists when they create a social profile. Especially, for people of colour, cultural identity has always been asked and highlighted, if not by others then often by themselves to have their voices be penetrated from the treatment of ignorance.

Youjia Lu (YL): In these days, I am often thinking of the meaning of my Chinese name. When it is translated in English, it signifies the meaning of sojourner. I feel more and more that this name speaks of the truth of my identity. I always feel that I pass by everywhere. I appreciate everywhere I stay, but then I'm not part of a place fully. So, when it comes to identity, my instinct would always resist of any identities. But at the same time, it is not like that I'm really tried to reject identity. It's like, if I say, I am a female artist, I feel not exactly. I'm not defined by the female itself. But then if I say, I'm not a female artist, it seems even worse than what I said before. So, it's always in this dilemma. If I say I am something, I am inevitably being identified with it. But there's something else that I feel that I also have, but not fully be identified with. If I say I am not such, that's felt not authentic either. So, I'm not rejecting any identities, but I resist of being fully identified with any terms.

SZ: You definitely speak of something that I have also thought a lot about as well. How do you identify yourself? is a very difficult, yet simple question. I feel like that you can always add on adjectives before the noun. I would say you are an artist, right? And a visual, female, Chinese Australian artist…You can keep adding on. No one can question about it, because it is what you define yourself. But at the same time, when you really think of those words, problems appear. I think everybody is a multifarious entity, not only the people who have a diverse cultural heritage. To say one (identity), you deny or ignore other possible identities you are/might be. It is a question that hardly can be answered in full satisfaction. I think that's probably the reason that artists often change their biographies. Five years ago, my artist bio was very different from my bio now.

YL: I guess that identity cannot be pinpointed. It's like I am who I am. I am really sure the fundamental truth about how I am. But I cannot easily find the equivalent to who I am.

SZ: As an artist, how would you introduce yourself?

YL: I guess I would try the most fundamental and broadest one. I am a human artist. Hehe.. (SZ: That’s legit.) If you identify me with female, I wouldn’t disagree, because I am female. But, I wouldn't highlight that.

SZ: Would you highlight that you are a video artist?

YL: Yeah. I am tied more with video, just because it seems inescapable in my practice. I do become to feel that there's a certain duty that I have with video. But at the same time, I am thinking to use the alternatives that actually wouldn't contradict (to video). Say new media. It would also make sense.

SZ: That's interesting. I would introduce you, first of all, a PhD candidate, then a visual artist and a video artist. But after hearing what you just said, I start to question how those medium forms are defined. When I think about video as a medium, I often think about its strong Western cultural root. The precursor of video medium is movie, and the precursor of movie is photography. And they are all rooted in the Western culture of technology invention and development. Now they are all different art media. There's a video art, there's movie and there's TV shows. Photography still exists. The social media technology and online publishing platforms have made the authorship of video medium to expand. In last five years, video works have been transformed so much. Sometimes I feel we may be on the cusp of the post video media age maybe.

I know you hold a PhD project that is based on video medium. I would like to hear about your relationship to this medium. How do you attract to this medium? Why do you choose this medium? What's your understanding on this medium?

YL: I relate the question about video medium to my identity. I feel that I’m meant to be a wildlife saver or something. I always have a mission to save something. Of course, it's a kind of novelty to talk in this way. But I guess that my empathy with the video medium always has been rooted there. Every now and then, I fall into this despondency of thinking how pathetic to pick up this media in my research, which is arguably not even exist anymore, Perhaps.

SZ: That's very interesting that you think the video media is extinct.

YL: It also gave me the passion to work on whatever I can to argue that it's not the only end of the story about video medium.

SZ: Why do you think of video is on the way to extinction?

YL: If you interpret my work as new media, I would argue that that's wrong interpretation, because in a way, it is not exactly. You can't really pinpoint what actually the medium materiality is anymore. From the perspective of a new media, everything is swallowed into that term.

The reason that other media I found are not as in danger is because they still have a really strong materiality that they can sustain. For instance, photography belongs to print media, even though it is digitised. But it still has a foundational base of its materiality. Video medium is rooted in partially new technologies, for example the handy camera. It is also an expansion of performance art. When video art started, there were a lot of direct confrontation with the broadcast channel. At that time, the mainstream used this technology to create TV programs. Then, video art gives itself an identity by opposing the mainstream. But when it is transformed in the digital format, it loses the purpose of it. I’m always really fascinated by the analogue video. I wish I was born in that period of time. It’s because there would still be the materiality of itself that you can experiment with. It was the physical format. When you plug in things, it actually generates a physical effect. That's something I think gives life to art practice. But when it becomes digital, it's really hard to preserve that experimental ground. Everything becomes a readymade for you. It takes an exchange to the convenience of how you can approach certain result. Then, you lose the thing itself in the exchange.

SZ: It sounds like what you define video medium in a specific art form that is descended from the 60s and 70s’ experimental film. In my opinion, the video medium is thriving now. It is not just because now the equipment to make videos is easily accessible. People can use their phones to make little video clips. But, due to the COVID break out, suddenly, our access to physical space has been reduced. The art space has very much moved into the online platform. E-flux just had added a video film section this year. In this section, lists of video works are curated by internationally established artists and published periodically. On the online perform, all art forms are transformed as video. In this sense, you see the increased number of so-called video works, right? But I guess my question is: can you call all those videos the video artwork? From what you said, I guess you believe that's different. Most of video works are presented as a narrative form. They use the video medium to convey a story. The medium itself, I guess, they are not really addressed. If we identify the experimental films in the 60s and 70s as video art due to their experiments on materiality of film, now, you are experimenting digital medium in your video works. My question is: Does the video work about the materiality of digital technology fall into the same category of video art defined in earlier years?

YL: I guess that's my main struggle or battle I imagined in my head all the time. The medium is the message is provoked in the 60s and 70s’s video practice. But for some reason, that we seem to lose interest in media. We only focus on our messages. Everything is serving this message. What if there is no message? The medium becomes the message. When you talk about last year when a lot of things were pushed online, is that the equivalent to the message itself? What if the message itself is the media?

SZ: Yeah, in that way, that moving everything online in some aspect is commenting on that medium. Everyone has started to be aware of the digital quality of the video suddenly.

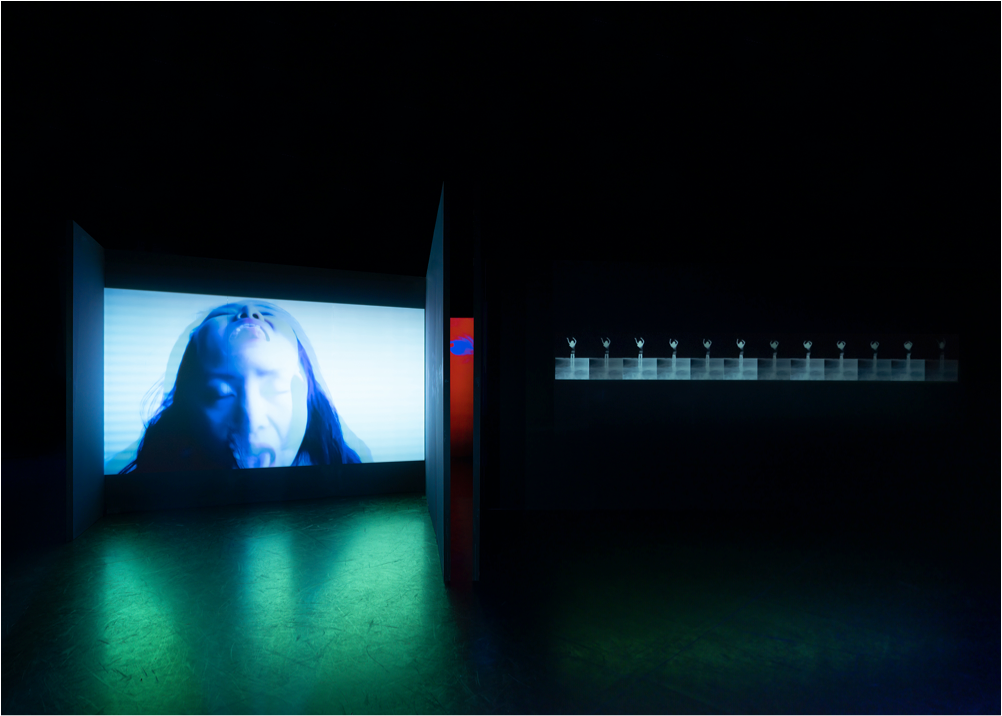

I saw your works at your PhD completion exhibition and also read the abstract of your PhD paper. It's a really impressive and ambitious project. Your PhD project is called Indeterminate self, and, I quote, “this project is identified as an Onto-epistemological predicament in experiment of video self-portrait.” Can you please elaborate more about this predicament?

YL: To put it a little easier. It's always this struggle that I consider of between seeing with the Self and seeing without the Self. It is the idea that in experiencing something, there's this dilemma between the sustained subjectivity and the moment of approaching something immediately. For example, may be helpful to think of a dream image. When you encounter a dream, what you see is very immediate. But when you try to recall it to a friend, and you try to capture with language which involves a process of reflection upon it, it seems to lose the fullness of it by referring to what has been processed through a reflection. It is because it's already through a subjective viewpoint of reflecting on it. So I pick up the dilemma of when we encounter something so immediate, like the world of ourselves, it has that fullness. But at that moment we cannot have in the fullness of itself. Once we are trying to see what I'm doing here in relation to that encounter, then we actually also lose that fullness of what we encounter by reflecting on itself. So, either you lose yourself in exchange of that immediacy, or you sustain back to yourself. Then you lose whatever the immediate experiences are.

SZ: I think that's a very philosophical thinking. What we see and what is presented in front of us can never be equal. Um, it's a bit similar to what I try to articulate in my work. It is that there's a slippage in every presentation. In a similar logic to your view, if we take a photo of a same thing, my photo would be a different photo as you take, same thing, but different (photos). And I'm interested in that slippage of presentational difference. We can't really see the full image because we don't have ability to see everything, but the bits we see create gaps.

You explore this predicament through this video self-portrait. Why self-portrait?

YL: The same reason as I pick up the video medium. I feel like everything in this research is full of paradox. I see this self is so problematic in this whole thing of approach immediacy. The subject matter of my videos are always exactly myself, which seems to oppose my intention. But I guess that's exactly what I hope for. It is with all this works to set up a condition that to provide such experience of that difficulty of trying to grasp or give a glimpse of that what you might get is something beyond what we see, or shakes that belief that what you see is what you see. But at the same time, it also brings the awareness that you are involved in this struggle, like yourself is the problem and the reason why you don't see things fully. I guess that my whole practice perhaps is always about that the self is often having this quality of opposing itself.

SZ: For me, I always have problems to position myself in front of a camera for my artworks. The uncomfortableness is derived from knowing about how Asian women had been presented in the history of Western photography. I always feel weird to look at the images of myself. I guess that's like what your argued in your project about the removal of self when you look at yourself.

When you edited your videos, do you feel that kind of removal?

YL: That's more like a numbing process for me. I just mentioned about Marshall McLuhan’s idea that medium is message. He had another point about the amputation of video image. In his view, when we record (ourselves), we go through a numbing process by producing a duplication of video recorded image. I feel more and more that is what I experienced when I worked with my self-image. I was so focused on the experimenting of the image itself. I almost stopped looking and thinking that's me anymore. It's like when you're experimenting with anything, you tune into the process of experimenting with the material. The images of yourself become just the material for you to achieve certain condition that you set up with. You stop seeing the object as itself except for whatever that context is. I always consider providing minimal identifiable qualities of me in the work. I do a lot of procedures to reduce as much as identifiable quality of me, for example, the skin colour. Of course, I can’t remove the look of a female figure. But it's always kept minimal. No cloth and other things can actually bring in any context to identify certain age. I treat it as the subject of a thought experiment. When you bring a figure to prove a point, you don't want to give extra information into the process. But at the same time, I am aware, inevitably, that people will pick up certain things that they want to focus. My approach is if there's anything to avoid my identity to be shown, I’d rather take that and hope to suspend audience’s attention on the content about identity. I always feel that my approach is quite antagonistic. The experience is not comfortable at all, because I set up a condition of an overloaded and excessive information. I hope this condition actually helps to suspend our contextual reading or our mental process of thinking in a conventional sense. When there's too much going on, we don't have time to process all. We just receive whatever it is.

SZ: How would you describe the style of the images you create in your video works?

YL: It's an illusion of a super-imposed image.

SZ: It's like to see lighting. It is a psychotic sort of imagery. It reminds me the flashing light often projected on the dancing floor in a nightclub. But in night club you don't need see particular things. Your work, otherwise, demands eye contact from audience. So, when experiencing your work, I feel that the impact of this lighting effect is intensified and enlarged. The flashing light effect successfully places the viewer in the predicament between seeing and not seeing. In your PhD paper, you stated that by creating this optical experience, you intended to make the liminal stage between the conscious and unconscious informed to the audience. I am interested in the link you make between the action of seeing and the consciousness. Could you please share your view on this link?

YL: Going back to when we talk about the immediacy. The subjectivity is sort of similar. When we're talking about seeing, it is something we can consider a conscious experience. It is often tied with subjective experience. So, it's always like, there is you to experience such and such. That is your conscious experience. But, there's a subliminal level. It is an experience that you don't aware of it. So, you can't really report that experience.

SZ: Does that mean when you can’t see, you are more in an unconscious stage?

YL: I guess there are a lot of things that happened too quickly to be processed into a conscious experience. But it doesn't mean we don’t actually experience it, or aren’t stimulated by it. I think that perhaps that is closer to the immediate experience. That is before we actually are able to process through what we reflect upon such experience. Once we start to reflective process, we become a filter. Through this filter, I see things that bring in certain logic of me, and reasoning of me into it. Like when we're talking about dream, I found like in dream, you can allow paradox. You can see things that are this and that. Perhaps something is both banana and avocado. But when I tell you about it, I cannot bring that in my referred story. Or, I would make a certain judgment on how coherent that story forms when I reported to you. I become my own filter, like a censorship.

SZ: For me, it's very hard to find an example of unconsciousness state. You did mention when you focus on the subject so much, you are not aware of yourself. Is that correct interpretation of what you meant?

YL: What I understand about unconsciousness is that on the subliminal level, like something is happening in a really fast pace, link in a split of second that way. It's not enough for us to process what we see, like a flash of something. But we're receiving it. The stimulus which is received orders us to react.

SZ: You saw something, but you couldn’t really comprehend or make sense of it.

YL: Yes. Something is below the ability of grasping it. But you still register it. it's just not yet an experience to you, because you haven't processed it to be a subject experience. It doesn’t allow you to process it into an experience of your own.

SZ: That's a very interesting perspective. In your paper, you proposed an imaginative scenario. It was once we died, our consciousness could be uploaded to a computer data archive and operational system. You asked in this scenario what is the conscious and unconscious? This is a core question in the current imagination towards the future. The popular TV drama West World is very much based on the imagination such future, and has made us witness a human world where this scenario was the reality. The development of AI technology and simulation technology in recent years has offered us a rich condition to allow us to think such reality would very much become a near future.

What I am interested in this scenario is when our thoughts and memories can be sustained outside a corporeal body, what is the action of seeing? Do we need eyes at all? Are eyes simply replaced by the camera lens? When the information can be received via various mechanic sensors, how does this mean of seeing affect the consciousness? Would this machine-operated living consciousness have unconscious moments? Do you think of those things too in your research?

YL: The only thing I can think of is that we do need a body to experience. It's hard to argue if we are always conscious. or if there is a continuation of consciousness. The thing that I'm curious about is the liminal state between the moment when you lose your consciousness and the moment when you get it back. Perhaps only when you experience the loss of it, then you understand what it means to you. It’s like the near-death experience makes you have more understanding about life. I guess it'd be really hard to imagine what the difference between me and a copy of me would be. Would they function the same? I think that experience of loss is a quite personal one.

SZ: How do you register the experience of loss into your consciousness? How do you aware that you no longer have something? Well, I guess it's a huge topic and very much the essence of post human discourse. Even if we don’t talk about future, nowadays, the way of seeing is no longer the same experience 5 years ago or 10 years ago. These days, seeing is constantly disrupted, there's no continuation. There is not even a start and an end. It is experienced as a collection of multiple glimpses. This is very much linked to the development of the new technology for visual presentation of information. On Instagram, we see images through continuation of swiping. We are used to the unexpected messages and images pops up during browsing and reading. Seeing becomes more like an experience of witnessing clashing moments of different narratives. We are exposed to multiple disparate things simultaneously. Nothing is read in a linear order anymore. We are forced to constantly make decisions on which story we need proceed, which moment we need return to. I guess, when you see a pop-up ad on your screen, the experience would be similar to what you said about the unconscious moment. You saw it, but you don’t register it in your comprehension.

The disturbance of seeing has reconstructed the way of thinking and the way of understanding too. The epistemological process has been shifted. Your video works speak of this current fashion of seeing and thinking. Many contemporary video works reflect on this way of seeing. For instance, Arthur Jafa’s award winning video works. In these video works, multiple aesthetics, narratives and editing technics are jammed together and form visual and audio chaos on the displaying screens. A new gramma of creating and comprehending video works has been developed. Would these videos belong to new media?

YL: My approach is rather to think of the limitation of things than to contemplate something difficult to identify. Sometimes our experience isn’t fulfilling. It is because our seeing has limitation. It is actually the limitation that gives a real experience for us. That maybe help us to identify who we are. This thought speaks to my practice. This limitation makes illusion possible. As we are not processing things we see fast enough, we see illusion. This is a quite unique part of our human experiences that we have that error. If we can capture everything, that will be great. But that's not our experience. My limitation makes me who I am, rather than my achievements.

SZ: Go back to the first question I asked you about identity. Fiona Tan concluded that she could only be defined by nos - what she is not, by the end of her journey that she set in her project titled May you live in interesting times (1997). In this project, she travelled around world to visit her relatives carrying the sir-name Tan and living in various socio-cultural communities. I could not agree with her any more. There is also a saying that identity and even authenticity are fictional. There is no absolute definition of who we are and cultural identities. Truth is subjective. On the other hand, due to the ambiguity of these ideas, we gain a freedom in expression of our identifies. I can call myself a Chinese, Australian, female, and installation artist. All these words construct a signification framework for people to interpret and imagine who I am.

I know your work does not address the subject of identity in a specific political sense. But the subject of self is prominent in your proposed questions. Also, video as a close cousin of photography has a great ability to disrupt the idea of truth. When I say video, I mean it in a quite general sense. All the videos circulated online and seen on various apps and the screens in different sizes, present us various parallel realities.

On other topic, I notice there is a presence of nostalgia in your video works. In my video work Sync, I pulled out footages from the TVs and movies in English language that i watched in the 90s and 80s and dubbed over the voice of the white female characters who dressed in Chong Sam. For me it's very extremely nostalgic experience to remember these old movies and Tvs and watch them again. It makes me realise that video is such a perfect medium to channel this kind of sentiment towards the past by allowing you to visually contact with people from the past or re-interpreting an aesthetic fashion. Your video titled Diffracting Locomotion particularly refer to the photo experimentation works of Eadweard Muybridge. This work is very nostalgic to me. Could you elaborate your attraction to the past?

YL: I think that nostalgic quality is tied with the history of experimenting media. I feel really lonely in these day. There's not many people experiment with me. So, I go and think about all of the past predecessors and how passionate they were in their experiment. I feel like they are my spiritual friends. Eadweard was one step away from being the inventor of the cinema. He didn’t make it, but he established the foundation of film technology. It makes me emphasize him about his experiments. Another thing that I have discovered from the past is structural film in the 1970s, in particular, Paul Sharits’s works. When I watched his video works, I felt really fractured. I realised that I was trying to use video to create something he had done in the past. But he did in film. My medium is digital video. I guess the nostalgia in my work is driven by this deep feeling that digitalisation is inevitable in video medium. In future, very few would care about how it displays in the space. Video will just be a virtual experience. If I have the last hope, I just want to find any possibility to set up a situation in which video can have a certain identity, like the structural film in the past. Maybe in a sense, what I'm doing is already not video, as I want to give video a certain body which is no longer even needed.

SZ: You give video a material condition to exist. That material condition offers a tangible experience. When you watch the video on a computer, its material condition is the material quality of the computer. But when you build an architectural structure at a site to place the videos, you give the videos a spectacular content and shape a particular viewing experience. I feel your attitude towards video opposes to the trend of the development video medium. These days, with the continuously enlargement of online storage space, video tends to set free from material bondage. The videos sitting in the cloud space, can be accessed with a correct directory. What you do is to pull down its reliance on a physical condition.

But what video medium will be like in future? We don't really know. With this context, the sense of time in your videos is not in one direction. Even though you refer to the experiments and video works created in the past, and use similar editing methods, your works will still be different from these works. It is simply because you are in a present time. Everything you do has this contemporary veneer and quality. New images are developed from the images created in the past. These images do not only signify the past, but also change the understanding about the past. So, we approach the ideas about time in a circular way. The old things are analysed, reused in the present and become a trend for future. It proves the theory that future is the past, and the past is the future.

My last question is about the sound in your video works. I think the sound is an important element to create a very effective experience. Would you like to talk about the choices in adding sound to your videos? How do you create those soundtracks?

YL: It’s almost completely coincidental. I was actually lacking consideration about the sound. When I filmed, I recorded ambient sound. The manipulation of sound in the post production is similar to how I treated the video image. I tried to stretch the sound to disguise what it was and made it unidentifiable. When I cut the video, the attached sound naturally is formed into a pattern of beeping noise by the gaps of the clips on the timeline. So, the sound completely was a by-product of how I treated video. Somehow, the sound becomes quite distinctive rhythmic patterns.

All my decisions are based on the principle. That is that I have less of decision making to do. That's why I am really in tune with experimentation. My role here as artists is always to work out how I can set up a condition to make what I have hypothesized. I try to avoid any decision making that is based on my own evaluation. If I make a sound scope, it will involve a lot of intention about how I wish it sounds like. So I keep whatever I have got from the recording and manipulate it in the same principle as I treat the video images of myself. All the footages are created not through an intentional recording. I recorded many random movements of myself and created a large database of the movement footages. I pick up randomly just less than a minute footage and experiment it with stretching effect on the editing timeline. In this way, the aesthetic does not always relate to my own judgment about if it looks good or sounds good. The video footage and sound are always a raw material for me to serve that function.

SZ: Have you ever thought of not using sound at all, like making videos mute? Generally if I'm not sure about the sound in my video work, or I’d like to encourage the focus on the image, I would make the video mute.

YL: I was once thinking of replacing the soundtracks with the more natural ambient sound recorded from natural environment. I guess I never haven't found a reason to get rid of sound.

SZ: I think a sound is another layer of narrative. Either you sync it with the video to enhance that what you see or you set it off to insert another storyline. For instance, I dubbed in my video. My off-tone voice squeezes a new narrative out from the images on the screen. It is something that you don't have to pay much attention to. But it is a quite distinct content when you watch videos.

YL: One thing I hope to chase once my PhD project is completed is that rhythmic quality of everything. That would open up a new lot of other researches.

Siying Zhou spoke with four Melbourne/Naarm-based Asian female artists to ask them how they navigate their racial and gender identities through their studio practices.

The four conversations are being released in stages.