Siying Zhou in conversation with Pia Johnson

Siying Zhou

Eurasian Identity. Photography. History.

While making work for the Blindside exhibition George prefers Forks, I read Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism. In this book, Anne offers a perspective with which to approach and understand the unique race and gender category of ‘yellow woman’. She believes that through this inseparable association with object hood (drawn from the technologies of embroidery, ceramic, robots and food-making), East Asian women can develop their own ground in the intersectional discourse about race and gender, and articulate a different kind of surviving history in Western society. In the beginning of Ornamentalism, Anne reveals that the critical race and gender examination of ‘yellow women’ is insufficient, and still tends to follow the theoretical frame that was created in the 70’s. She underlines the fact that we still know very little about East Asian women while the race and gender of ‘black and brown’ women has been constantly examined and studied along with the social changes in the Western world.

When I read Anne’s argument, I recalled a moment when a female curator who has Asian cultural heritage casually revealed to me that she was sick of the topic of the Asian female body in the arts, implying that this subject was overly explored and had became monotonous. My question is: how could we be sick of something that we know so little about? As Anne draws her evidence from American history and mainstream culture, I wonder how Ornamentalism is applied in the Australian social and geopolitical context. Could Ornamentalism provide a place for East Asian women in Australia to grasp their existence? More importantly, how does the Ornamentalist perspective reshape the quintessential tradition in Western Art of examining the materiality of artistic media and insert racial and gender context into such an examination?

While I was contemplating these answers through the process of manipulating images and objects, my research into the Australian past and my examination of the sartorial relationships that a Chinese woman could draw, I spoke with four Melbourne/Naarm-based Asian female artists and asked them how they navigate their racial and gender identities through their studio practices.

This is the edited transcript of the conversation between Pia Johnson and Siying Zhou via Zoom on March 26, 2021, took place on the unceeded lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation and Dja Dja Wurrung country.

Siying Zhou (SZ): I know that it is a repeatedly asked question. But I still would like to ask how I can describe you, a photographer?

Pia Johnson (PJ): Yes, you can describe me as a photographer, but ultimately, I’m a lot of other things too. I find introductions or how we want to present ourselves, can be quite complex. Through my PhD, I describe that we perform our identities. So, we shift to whatever context that we're in to make sense of our belonging or not belonging within that space. I think there's a standard line that I have in every bio: Pia Johnson is x y z. And it's usually includes visual artist and photographer. Some people asked me: why don't you just call yourself a photographer? or why not just a visual artist that utilizes photography? I think it's partly because I come from an interdisciplinary background. I want to actually claim the history. I've got textiles in my background, I've got creative writing in my background. I've got all these other disciplines that sit and influence whatever I make. Sometimes it (the work) does become an installation. I do use video or found objects. So, I think that's why professionally I say: I'm an artist.

Recently I also may include more clarifications: female identifying and mixed cultural race or Eurasian Australian. All these qualifiers to being an artist. I do think we actually shift our choice of identity and find the things that we are, depending on the time and place. It's all about, what Anthias Floya talks about translocational-positionality. Where are we? What time are we in? What context? Who is speaking to? I think that really affects it. Essentially, I would say, I'm a visual artist and photographer. I come from a cross cultural background of Chinese and Italian Australian heritage. I live regionally on Dja Dja Wurrung country. I'm female. I'm a mother. I'm an educator. Yet on some occasions I just want to say I'm an artist.

SZ: I know exactly what you mean. I can tell you what I just did, for the first time in my life. When I put down my signature for an open letter circulated within an artist group that I am in, I added my paid job position along with ‘visual artist’. That is Support Worker for People with Disabilities. “Why not?” I thought when I saw most people put down an array of titles next to their names: artist, writer, curator or producer or performer... It is a privilege to be just defined by the art jobs as an artist. But as far as I know, many artists, like me, have to take on a life nothing to arts to support our engagement and status in the art. And why are we so reluctant to tell the art authorities about this non-art part of life? Why is there this feeling of the less if we tell people the job we take for making a living and that is not in the art? So, I did it to shake up the convention of identity politics that we are engaging in on a small level.

PJ: I know the letter you're talking about. That's a tricky thing. It's not just about marketing, it is actually also valuing what you do. It means that I have a whole lot of experiences and expertise, and understanding of a particular sector that I find important. That's what you're saying.

SZ: I know that all works that I do have value to me. But the value of things I do might not be seen by others. This is why it matters, how you present yourself to others. Most of time, we are discouraged to put irrelevant information at a formal situation, like when you're writing a grant proposal. You want to feed to them what they asked for. Giving ‘not required’ or ‘mis-context’ content would cast a bad impression on you or disadvantage you in the application process. That's why I think we are forced to strategically put down the words for our bio, and titles. It sometimes feels ironic to navigate in the western art culture. On one hand, we are encouraged to discover who we are and be open about who we are. On the other hand, our creative activities are framed or manipulated by the power structures in the arts.

PJ: We live in the real world. So, we have to function in that. I mean you can choose not to. But I think for me, I've chosen to sit in that structure. And also, I think being a Eurasian, which is a relatively new term and I've embraced for a range of different reasons, is also acknowledging that I have a privilege of passing for white sometimes. You know, not all the time. But, there is that fluidity that I'm allowed to potentially move across more communities or more sectors easily than others. I'm probably not as radical as a number of other artists who want to give away the western canon or the white narrative, because I'm still aligned to that. Stan Grant talks about it brilliantly. Being indigenous, as well as understanding and not wanting to forget the history of his white heritage in his family tree. Obviously, the Indigenous and First Nations experience is a very different structure to the migrants that have come here post colonisation. But, for me, I look at my parents and my grandparents. One set of great grandparents came here and didn't fit in, even though they were white, in our terminology now. But back then, they weren't. They were foreign and migrants. So, I think it's really complicated and I find it difficult to talk and define some of those things.

SZ: It is a muddled place. I know exactly what you mean about the confusion tagged along within the identity of being Eurasian. I think it’s not just you, lots of people, especially people who grew up from a culturally diverse family, have this sort of confusion. It's just impossible to give a fixed identity to anything.

PJ: Totally agree. I think if we let go of identity politics in a way, we could be really free. I mean it hypothetically, but I think there'll be a lot of pressure taken off.

SZ: I guess there is a reason that the narrative about artists’ personal identities is valued so much in the arts. Arts have provided an important public platform to hold the voice of people who are considered in the peripheral social communities. The challenge is how to place political content inside the art spaces. Maybe I'm thinking more about the art institutions. When I read the exhibition programs in major art institutions, I often find that value about the artist identity has surpassed the quality of the artworks. As you said before, in some exhibitions all I read are the boxes the works tick, instead of arts. I have developed an ambivalence and reluctance towards the identity politics. When you claim what you are, you also tell people what you are not. But are you really rejecting other titles? As much as I find it problematic, I know that my art practice deeply has tied in the discourse about identity. As an immigrant, I can’t escape from it.

PJ: I'm grateful that you also feel like that, because I think the problem is that you have to be really concrete about it. You have to really define the box that you're sitting in, or the territory that you're mapping out. And that can be uncomfortable to do. For a long time, I felt I was labeled as the cultural identity chic. “Get Pia to talk about cultural identity, because that's what she does.” But it's not everything that I do. I think sometimes it is easier to put people in boxes or define ourselves, as society wants us to do this. But actually, human nature is not like that. Partly because of the PhD, and my practice over the last decade, I have realised that I have used cultural identity in a very particular way. I use a personal story to connect to other people who may not have the same background or the same very specific parameters, and through my artwork I hope to give them a way to further think about universal human kind of problems or concerns. Once I connect to those people in that wider community, I can make them start to understand my perspective. It’s like a circular kind of formation.

SZ: I think your work is not only about your political agenda but also artistic provocation. In the current political trend, often the concerns on artistic value is shadowed by the concerns on the political message. In the making, sometimes we don't really have a great explanation why we do this or why we create this image, we make decisions under an artistic instinct. But this aspect of making somehow is often neglected in the art program, or only discussed on a surface level.

PJ: Yes, it can become about the politics rather than the art itself.

SZ: Let's talk about the materiality, the figures or what you feel from what you see. I feel like those things are boxed in an academic boundary. They only are talked about at school. Once you're out of the school, people don't want to hear about them and or think they are not relevant. Maybe let's talk about your artwork.

PJ: If we talk about materiality and bodies, obviously I put myself in my work all the time. Originally it came from needing a body and not having any money to hire a model or alternately working in really odd hours. When my daughter was really young, I had anywhere between 20 minutes or 90 minutes to make work every day at home while she was having a nap. I look at that equation and decide, well, if I want to put a person here, I have to put myself in there first. It's just basic math. But what I realised is that this has become its own language. A couple of years ago, I used somebody else in my work. It was really hard. I have realised that I have actually created my own way of working my own shorthand that isn't necessarily there for a model or for another person. I remember one of my supervisors saying to me: “oh, you're not going to just make work about you again, are you?” And I tried. I used my sister, I used a few people that have a likeness to me, or a connection to me, or similar heritage to me, but it didn't work. I actually need to use me in the picture. I perform in my images as a way with a level of semiotics or symbolism that no one else actually can do. I embody something that no one else can do. So, whether I like it or not, for me to get the artwork, and the image that I want, I have to put myself in it.

SZ: Can I understand that when you are performing in front of your camera, you perform another self, or another ego of you? It is not the one in your everyday life, but still you.

PJ: I am ‘me’ in my photographs, but I guess I am also the many ‘selves’ of myself. If that makes sense.

I think photography traditionally is very much a white and masculine kind of art. Traditionally it sits in that paradigm, even though there's lots of female artists and female photographers through the entire history of photography, working in incredibly nuanced and highly technical ways. The idea of a self-portrait becomes political here. It offers a really safe space for me. I'm the camera operator, director, and subject. I control the entire environment. So, I think you're right, I have the space to be someone else in the image. I can perform, I can play, I can experiment. It's subversive in one way, because I'm playing to my own gaze, rather than a male gaze or society gaze. It's totally safe. A lot of my work is within either the environments that I choose, or they're my home, or the domestic settings that I can create all the parameters. Even recently, just for fun, someone asked me to respond to some words. I just used myself to do that. And it's so liberating. In many of my photographs you may not see my face, or I'm not looking at the camera, but I enjoy using myself within my works. I guess you could probably come across it as really narcissistic. But it's also just a way of expressing my ideas in a way that is economical and evocative too.

SZ: Yeah, I think it is beyond the financial concern and practicality. As you said that even though you had enough money, you didn’t feel right when you shoot others. I think that there is a conceptual connection between this body in front of the camera and yourself. You have created this particular space for yourself to jump out this every day self and to interprets it in a different way. I think that's a really strong reason to use yourself in your work.

I can't really photograph myself. When I started making photograph works with an Asian female body, I had to use my friend. Luckily, she was available and happily volunteered with little rewards. I guess I can't jump out this body to be an alter ego. Also, for me, in-between the photographing subject that I see through the lens during the photographing process, and the subject seen later in film or computer screen or the print, there's always this gap. Whatever I capture at the site at that moment changes when it becomes a flat image. I wonder when you take a photo of yourself, you can't really see yourself when you take the photo. When you see the images of yourself in the post production, in a 2D dimension, what do you read that body? What do you think you see? Do you experience the slippage as I experience?

PJ: That's a really interesting question, Siying. I don't think I've ever really thought about it like that. I probably don't ever see that the photograph is flat, either. I feel like it is a world. I feel like the photograph shows me a really good short story. This tiny split second of life, obviously, if the photo works. There's narrative in this story, and there's a before and after moment in the image for me, I think. While it is removed, I don't necessarily see it as me. I don't necessarily see it as somebody else, either. I think I'm actually really just invested in the world that I'm trying to create. That's probably the best way of talking about it. I did a series recently in a big heritage home in western Victoria. I did take on a character for that. It was quite interesting. I actually wore particular costumes. For this particular residency, I became a bit more theatrical, I guess. I chose a period style vintage dress because I was sitting in a heritage kind of space. I put makeup on and did things that I would not necessarily do. So, it did have a more theatrical performative feeling to it. Not to say that the other images that I've made myself aren't performative. They're just working at different narratives.

SZ: In my understanding, you performed a self, according to the environment that you were in?

PJ: Yeah. I make decisions while I was photographing. So, in that scenario, I was responding to architecture, to light, and to the history. That particular space was really fascinating because the woman who owned it, was a Hollywood star from Canada back in silent movie time. I took this into account when I was composing ideas around the house. I'm influenced by the environment that I am in. Comparing to the space in the Eurasian in Singapore series that I did, where I went to Singapore and put myself into the photographs, this functions completely differently. In Eurasian in Singapore, I was trying to reveal how and why I was in Singapore. It was in response to some critical feedback I had got within my work in Australia where I was very much seen or I played to the Asian body, my yellowness, even though it's probably more olive.

In Australia, generally I'm seen as an Asian body or Eurasian, but the Asian bit is always seen first. And I always joke that it should be called Asia-pean, not Eurasian because even though the power structure is typically in the western canon - Western over Eastern. But here my experience is that I am always seen as Eastern before I am acknowledged as Western. So, for me, I should be Asia-pean Australian, not Eurasian Australian. I'm seen as an Asian body. I think that how I grew up has influenced me. The difference was the Asian difference. My mum is Chinese Malaysian. We celebrate Chinese New Year. I have a Chinese middle name. It was all these Chinese things that stuck out and were different in the monocultural 1980s Melbourne suburbs. Having that experience, I think, has definitely shifted and influenced who I am now and who I feel connected to. Not to say that I'm not connected to my Italian heritage. But I think just that my Asian appearance means that I'm always asked if I'm an Asian descent.

SZ: My understanding about why your Asianess is always seen first is that there's a long history of how Asian women, especially Eastern Asian females being depicted as an aesthetic and a symbol of exoticism in Western society and art. A formulated artistic grammar and language have been developed to portray Eastern Asian women. For a pair of western eyes, it easily is drawn on the familiar signs of the ‘Asian’ content. But the irony is that these easy contents in their opinion indicates very little that they know about the subject.

I’d like to talk more about the series Eurasian in Singapore. I feel you purposefully displace yourself in the social environment of Singapore. You wore black in the middle of the crowd in which none of them were black. The black probably is the least favorite color in Asian cultures, as it symbolizes death. Your face was unanimated. You stood straight. All of these makes you separate from your immediate environment.

PJ: The reason that I chose Singapore is not only that my relatives are from Singapore and my aunt still lives there, but also that it has the largest population of Eurasians. It has this massive history of Eurasian culture, which is quite incredible. The research is amazing. They're trying to save Eurasian languages that have been lost for years. They are trying to record them. I use the artistic device of being quite blank faced, still and facing straight at the camera and dressing differently to present myself as displaced. I felt displaced when I was there. Ultimately, I feel that I belong to Singapore. I can smell Singapore when I just think about it. I love the food. I love the way people move. There's so much about it that I love culturally. I feel at home in that space, but I'm not at home. It's like an imaginary nostalgic home. When I'm in Singapore, it's quite interesting, because I come across as a foreigner. I possibly could be there because it's such a huge mixture of cultures and lots of expats. There are two places in this series. One is that you talked about, is in the classic marketplace or food hall. The other is where I'm by myself in an expanse, and those colonial places where the British colonies resided originally. There is really weird black and white architecture, very British, with typical colonial aesthetic, and big wide expanses of green grass. In amongst the people, I'm separate. When trying to be part of this British Western colonial legacy, I also don't fit. I'm so alone. It seems weird with or without people in the hustle movement, or color, or subdued, or the black and white landscape. The content informed in the works is so other, like the perpetual foreign concept, never belonging, but trying to always be in it. I think that is a really interesting point, because it's the same in Australia.

SZ: In this work, I feel that you removed all the identities of you in the images. I don't know who she comes from. You are like a void. In your other works, your identity is kind of quite clear, such as Family Resemblance, after Wittgenstein. In this work, you particularly chose different artifacts and part of your body to indicate a reading about a culture. They are like the token of Chinese and Italian cultures. The object, itself articulates a clear cultural signification. Did you create this work first or the series about Singapore?

PJ: I did Family Resemblance, after Wittgenstein first. It is the circle work with all the objects. Eurasian in Singapore was in response to that, because I got some really interesting feedback about that work and the notion of playing to the stereotype, using objects as symbols. For me, that work really does symbolise the collective of social and personal cultural identifications that we all carry around with us that make up our identity. It’s not just us solely walking around the world, it's where we situate ourselves, how we dress ourselves, how we perform, what we collect, what we hold dear, where they sit within our family histories and migration paths and mobility. The circle work was really meant to be this massive big splurge of all the different things that can make up one's identity and play to those stereotypes, I guess.

SZ: I keep thinking about your posture in Singapore work. Most of the time, you stand up, not doing anything, which is a very different from your other works. In other works, you are in a some sort of gesture that indicates movements.

PJ: I'm like a prop (in the series Eurasian in Singapore.)

SZ: Yeah. You seem objectified yourself. I could also interpret it as someone who was mourning. Especially you wear black. There is a reading of sadness. Did those things come up into your thoughts and consideration when you were taking the photographs?

PJ: Initially no. Initially, it was exactly what you're talking about. It's just instinctual response. I was going to put myself in this environment. This was what I was wearing. This seemed fitting. I think I purposely wanted to cover my legs. I also realized it was quite a spectacle that I was creating. Usually when I create works, there's not many people around. But all of a sudden, I'm putting myself into a very busy scenario. Setting up a camera, I had a student helped me. I set everything up, but had to have him press the button. Usually I work with a remote. But I just thought because there was so many people around and (considering) safety and security. I had him just stand with my gear, and press the button. It was quite funny and weird because I was directing. I told him to press “now”. I curated all of it. I think when I saw the very first image back, I then went, that's what I had to keep doing. It wasn't planned. I did spend a lot of time walking around and trying to find locations that I liked. One that you may not have seen is in a classroom scenario. I was there actually as an artist in residence at the National University of Singapore. I used a particular class to set them up and put myself in there. It was probably the most different out of all of them (the photographs), because there were so many bodies of doing their own things. They were young bodies. The effect is still the same. I'm still like deadpan, looking straight at the camera at the center position. I realised that worked. It was truly just from looking from making the work. I wouldn't have been able to plan that.

SZ: I feel there is this uncomfortableness in the posture of standing straight, where the sense of disconnection and displacement are conveyed. On the contrast, the animated body in your other works, informs a confidence and comfortableness that you had with the space your occupied. It’s like to look a statue in its public space. The contrast with the lively street scene always projects a sense of incompatibility and alien-ess of the statue. In this work, you were performing a statue, I guess.

PJ: In terms of performing a statue, I recognised that I had an audience when I was making the photographs. There was an actual spectatorship in doing it. Some people would wait for me to move or didn't want to be in the photos. They would take a different route. Others would just stand around and watch me taking the photos. It was weird. There was a lot going on.

SZ: This reminds me the experience of being a tourist. When you take photos at sightseeing spots, you deal with the crowd around you, both the crowds of residents and other tourists. In thinking about identity, when you were taking photographs on Singapore streets, you were experiencing multiple identities: being a foreigner, tourist, and an artist. Sometimes, what you experience during the photographing is not necessarily seen in the final artwork. I guess that what I am always interested in – the discrepancy between the experiences of the making and the narrative of the final art objects. Sometimes, one informs the other. Sometimes, they are completely two narratives.

PJ: The work that has more Asian specific female or feminine concerns is the work called Into our first world. I try to think through the notion of cross generational cultural performance. There is the image in this work that is of myself in a Cheongsam celebrating Chinese New Year when I was around six. The setting was in my grandparents’ suburban backyard. There were all these weird, different synergies going. But I felt that I was like the perfect Asian child, pretty in a pink Cheongsam, hair clips. I probably was singing something. The dahlias were in the background. They were the pride and joy of my grandfather's garden. It was this celebratory significant cultural moment in Western culture. It meant one thing to my parents and to my grandparents. But when you look back there is this aspect of objectification, maybe, but innocently. There is also this allurement that means for me nostalgically. Then in the series, I explored lots of pinks flowers to speak to darker undertones. I put a flower in my mouth. It was quite nodding to sort of feminist artists, like Georgia O'Keeffe and Judy Chicago. There was one that I wore a night singlet with an embroidered flower. In and out, I play with the cinematic viewing experience of what the focus is. Nothing is overt. It's all just sitting under the surface. As you never see me completely, it means that there is again a weird disconnection. I am an attractive woman confident culturally and in the world. But I don't want to just be seen as that.

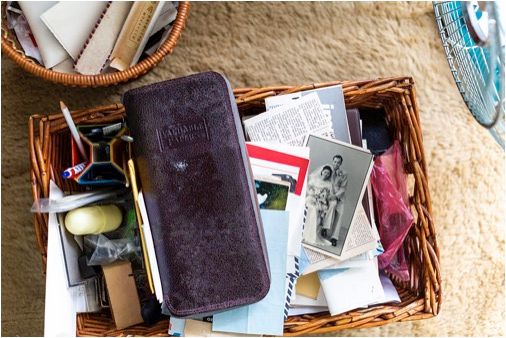

SZ: What I am interested in is this personal and universal sense of nostalgia in your works. Your grandparents’ houses are often appeared in your photograph works. These images contain a quite strong sentiment towards to the past. In the work Remembering Por Por, I read a conjunction between a sentiment towards the past carried by an immigrant and a granddaughter’s intention to preserve the life of her grandma. In this work, you placed the black and white photographs of your grandma together with the personal objects that she owned at different places of her house. I think, this work challenges the categorisation of photography. Are they portrait photos or the photographs of still-life? But more interestingly, I feel that these images reverse the equation of objectification of women. The objects in the photographs do not necessarily have a particular cultural reading. They could have been read as miscellaneous domestic items. But when a B&W photo featuring a young South-East Asian woman is placed next to them, these items immediately are given an idiosyncratic history and a cultural narrative frame. The imagination towards the woman in the photograph, her cultural identity, her personal history, becomes the axis of the fictionalization of the objects by the viewers. So instead of a corporeal body being turned into an object, in this work, the reading of this woman body makes the objects alive.

PJ: I really like this reading, because I think that's the point. This work is emotional for me, obviously, because it was about my grandmother. The original work, which is called Por Por’s house, presented a suburban house, except that all the pictures on the wall are of Asian people, or a lot of the objects featured are Chinese things or odd collections of stuff that you don't know how to read them together, but then having an identifiable thing that then makes you reread the picture. One of them was a bedspread. Someone at an exhibition opening came up to me and said: “Oh, my grandmother has the same thing. But she was not Chinese.” It’s not the point. Knowing that anyone in Australia can own the same bedspread is fine.

SZ: how did you make the decisions, when you created these photographs, for example, of which photo you chose to be photographed, and about where you place the photo?

PJ: That was a really interesting point when I did this work. My grandmother had just died. The house was being really emptied out. Stuff was all everywhere. All of a sudden, I saw the object that I forgot about, or tried to find the things I remembered. The thing that is not relevant or revealed in those images is that my mother was present when I photographed this work. It was a practical thing, because I needed her to be let into the house. There was a multi layered significance at this shooting event. My uncle ended up collecting a lot of my grandma’s things for safekeeping. I felt that it was my last time I got to look through all these albums of images. I decided that the ones that I responded to, were the ones that were very well photographed, and talked to her full journey, like in some critical key moments, the moments that we can understand. For example, the wedding photo, the photo of a young woman in a nurse's uniform. These images are more universal, right? They're not necessarily cultural kind of moments, culture as an ethnic culture. It is a broader social, cultural kind of moments in our societies. When you buy a new house, and you stand up front and take a photo of the house. I’d like to choose the photographs that mark those moments. I also took the pictures that I just adored and show her through her age. She lived an extraordinary life. I felt there was something about putting that in. In terms of picking where to place the photos, it was really instinctual. I can't really talk a lot of that. I would see something and thought that I had to put this picture here, or I was going to frame it like this, or when opening up one of her drawers, I thought I had to something in. It wasn't conceptually planned. It was so about being in the moment.

SZ: Most of the photos of her you chose are black and white. You did say that there were color photos of her as well. Is it a deliberate decision that you want to use the black and white photos?

PJ: I think there might be one or two colour photos that are included. There's one in the bathroom against a pink wall. It has a color image of her. I think I like the performative nature of the black and white against the colour. It is the aesthetic choices.

SZ: For me, black and white photographs take you to a kind of particular time. They signify the social narratives about the 50s and 60s, whereas, the colour photographs for me have strong narratives about the 80s and 90s.

PJ: I don't include any contemporary images of her. There's a point of that.

SZ: I think it's interesting choice. This choice really frames narrative about your work. The protagonist is read as a young woman in a further past.

PJ: Another work that I did, called She that came before me, which you saw at Manningham gallery. The exhibition included some old photos and a video work. I realised in that exhibition there's less time that we have had to understand and contemplate contemporary images. You saw one image of my grandma in her late 80s in the photographs. But the presence of her face, when she was in her mid 90s, was so much more evocative in the video, with my mother, and talking to time and all those things. I think you read it differently. Our proximity to contemporary images means that you read them differently. So I think if I had put a contemporary images into the series Remembering Por Por they would have not had the same resonance or nostalgia as the older images.

SZ: The black and white definitely nails that nostalgic tone. It would be a very different work if you used the contemporary photos of her in Remembering Por Por. Nostalgia is a fashion genre. I think the nostalgia provoked in this work is counter to the mainstream culture of nostalgia in the western society, because it indicates a personal history and a social memory that are not shared by the majority of population in Australia. This nostalgic feeling is very much attached to what being Asian and being Asian women mean in the Western society, and is embedded in the life of immigrant. The desire for a disjointed past always hunts the immigrants.

PJ: I think that for the first generation Australian, that nostalgia is still present. Sometimes I talk about trauma being passed down across generations. People ask me, why I am photographing my grandmother's house to talk about Eurasian identity. I think it's so prominent in my life. The materiality of those spaces, and those objects, and those photos totally have influenced my identity.

SZ: You did another work in Wollongong, NSW, in which you also placed personal old photographs among the objects. These photos and objects belong to another family rather than yours. What was the difference in creating this work?

PJ: That was a commissioned work. It was a really interesting process. I actually did what I did to my own personal history to someone else's. When I did it, I realized that I was working with archives. In my Por por’s house or Nonna’s house all these objects and things have become living archives to me. We all have them. I've just decided to call them this. Then I walked into a literal archive when I was working on Observations of the family table. This family in Wollongong had kept everything, rooms, photos… There was this one man in the family. His job was bestowed on him. It was that he had to keep up this legacy. While they were really famous about buses, because they're a big bus company in Wollongong, they also had all these other incredible stories, such as the lines through their family that weren't talked about. One brother was literally sorting through photos. He was a photographer. I think that was part of the reason why he got given this job. But there was his sister, who didn't live in Wollongong anymore who had a very slightly different relationship to the family history. She told me that she was always really sad that when things were told about the family, it was all about the brothers, the mens stories – especially about the bus drivers. She said that all the women made it possible. There was lots of sisters and aunties. They were always cooking and always mending. And they were always doing all the book work. They were doing so much stuff, and never appeared publicly in the archive. It was such a really interesting story to hear. In response, I created a video work about her looking through these images. To that point, she said, some of the aunties fought over how to identify who were in the old photos, because their names were not even documented. I find that is really fascinating. Today, one brother still owns the bus company. It is still very much lauded and the legacies are still about the men in this Chinese family, while all the women have disappeared in time. I think that's universal. It doesn't even matter what culture you're from, it still happens. Women fall into the holes of history or the pages of history. I wanted to speak to that and to show the actual process of what it is to archive your own family memories.

Siying Zhou spoke with four Melbourne/Naarm-based Asian female artists to ask them how they navigate their racial and gender identities through their studio practices.

The four conversations are being released in stages.