Working with Weeds Interview #1

Anna Dunnill

Full Nettle Jacket. Gleaning clues from fairytales and archaeology, Allan Brown makes cloth from nettles

In the Hans Christian Andersen story ‘The Wild Swans’, a young woman seeking to break an enchantment is given a seemingly-impossible task: she must pick nettles from churchyards, crush them into flax, and weave eleven shirts from the thread. Evidently a painful and difficult process, this sounds about as absurd as spinning straw into gold. But there is truth at the heart of the story: nettles have been used for cloth since pre-historic times.

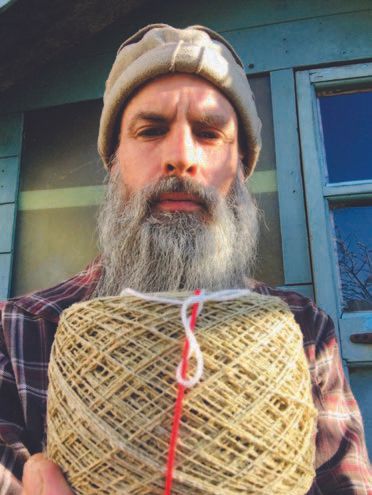

“Nettles are the fibre of the landless,” says UK-based Allan Brown. Since 2015 Brown has been experimenting with making cloth from the common European stinging nettle, Urtica dioica, in his project Nettles for Textiles.

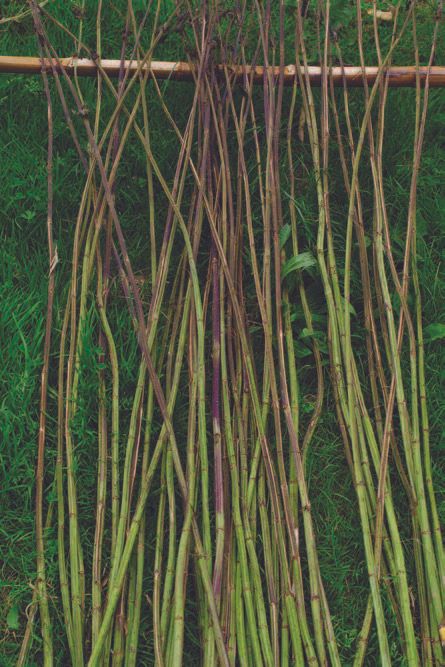

Like linen and hemp, nettle cloth is produced from long fibres extracted from the plant’s stem, called the ‘bast fibres’. To do this, Brown harvests wild nettles from local woodlands and strips the foliage off the stems. These are laid out on the grass and exposed to morning and evening dew—a process called ‘retting’ (literally rotting) which breaks down the pectins, lignin and other gums that bind the fibres to the stem and each other. The resulting strands are then scraped, carded and cleaned—and at the end there is a handful of fine, soft fibre, ready to be spun and woven.

While refining his own nettle fibre processes from trial and error, Brown has also worked with archaeologists to identify Neolithic techniques, and is hopeful about how nettles might contribute to a sustainable future.

Anna Dunnill: How did you begin experimenting with nettles?

Allan Brown: I was doing lots of walks in the countryside, and I used to take a wildflower book out with me, and start to identify some of the plants and work out what’s edible. I kept coming back to nettle as being the most readily available source of food, and so easily recognisable. And then trying to make cordage [string] out of it—stripping the skin of the nettle and twisting it into cordage. In the process of hand-rolling it and manipulating it, I could see that within the rough bast were these finer fibres that looked like they could be spun and woven into cloth. I thought, “Has this been done before? And if so, how was it done?”

I didn’t know the fairy tale ‘The Wild Swans’ until later on, but there are some real clues in there! It probably historically has always been quite difficult—it takes a lot of work. That kind of figures in the fairytale, where she’s tasked with what seemed to be an impossibly difficult task—to make eleven shirts, which at the rate I’m going really would take a lifetime! I think that gave me a clue that it is a difficult task, and therefore probably always has been, down through history.

AD: There’s a huge online community that’s grown up around the Nettles for Textiles project, with a lively Facebook group where hundreds of people are contributing to this body of knowledge.

AB: The whole thing has really taken me by surprise. My friend Dylan put together this beautiful little film [of the process], which far surpassed the basic ‘how-to’ that I was hoping to put across—and then it just went totally viral, just completely unexpectedly. It was viewed by so many people from all around the world. And I thought, “Oh man, I’d better try and gather these people, and have somewhere where we can discuss and talk.”

The great thing about nettles is that it really is the early stages of rediscovering—or kind of reinventing—an old art. And I figured the more people experimenting and trying it out, the faster we will learn how best to do it—which is exactly what’s happening. One person could work a lifetime trying to work out the next step, or a better way of doing it. But when there’s lots of people doing it,

all the ideas come flying.

AD: How far back does nettle fibre go?

AB: In Neolithic times, early Bronze Age, nettles were being used—in Europe at any rate. There’s been an archeological dig in Cambridgeshire, at a place called Must Farm. These round houses on stilts built over water had some sort of fire calamity, and [around 3000 years ago] the huts fell into the silty mud. And in at least a

couple of the huts, it was a textile-based operation—they found these little balls of fibre and bits of fabric, and they know it was nettle. It was being processed at a really high level—really, really fine, fine threads.

And in one of the Danish bog burials [of a similar period], they could

prove that the cloth was nettle—and that even though nettles were available in that area and grew abundantly, the nettles in the grave had come from a few hundred miles away. So there was obviously, I think, already a degree of expertise and specialisation going on; and the transportation and trade of nettle cloth.

The one thing that I’ve got from working with nettles is just totally reappraising the value of cloth, and just how precious it would have been. It would have taken whole communities working in order to create the time for some people to put in the levels of effort required to do it—but they clearly were doing it.

AD: Can nettle fibre contribute to sustainability in the long-term?

AB: There is actually a German company, the Nettle Fibre Company, which is quite far down that line—they process hemp and nettle in quite large quantities. There are farmers growing nettle around that area in Germany, supplying this factory which is processing nettle and extracting the fibre in a pretty environmentally sensitive way.

The model that seems to be growing is that nettles are an ideal crop for turning heavily chemically-grown cereal crops back into meadows and more balanced soil. So you can put crops of nettle in and get this useful fibre.

A lot of the use of hemp and nettle and flax worldwide is the contribution it’s going to make to composite materials—fibreglass, mesh netting, and all these other practical things that can be done. I was looking at it purely from a textile basis, but the uses are much more widespread than that.

It’s tiny at the moment, but any percentage of a finished textile that has nettle in it is going to a have a less damaging impact on the environment. One really beautiful thing about nettles is so many insects and butterflies use nettle as their food source and for laying eggs. Many other fibre crops need fertilisers and chemical pesticides and stuff in order to optimise it—but nettles can actually increase biodiversity, repair soil and give you a crop. It’s a healing crop.

AD: Tell me about your related project, Hedgerow Couture.

AB: Hedgerow Couture is really a place to collate all the other stuff that I was doing, which spread out from starting off processing and spinning nettle.

When I got into playing around with nettles, there was no forethought. It was purely like, “Can you get fibre out of nettles? Can you do anything with it?” As I needed to work out the next step of how to try and create a fabric from nettles, I had to pick up spinning, and then learn the basics of weaving, and one thing led to another. I started to get interested in, “Well, can I dye it? And if so, where are our local dye plants?”

I’ve subsequently learned about Fibershed—this idea of trying to create cloth from within a local area as much as possible. That’s really been my driving ethos. I use fleece from Sussex where I live, and I try and process the fleece and other fibres in as environmentally-friendly a way as possible, and then weave it. I grow flax on my allotment, and then nettles I forage.

Unfortunately it’s a terrible business model, because doing it this way is hugely labour-intensive! But having that as the driving ethos just sits most comfortably with me—using local plants, using local fibres. In a way, limitations sort of increase creativity as you try and find solutions. And the cloth that I create definitely has a stamp of the area that it’s all happening in.

AD: Your processes are obviously very seasonal. What are you working on this winter?

AB: When I first started fiddling around with nettles, the first thing I thought I wanted to make was a jacket. I thought it was a pun too good to miss—making a ‘Full Nettle Jacket’.

But then actually, because of that fairytale quality to nettles, I decided that what I wanted to make was a nettle dress; it felt like a more fairytale sort of garment to make. So I’ve been amassing fibres over the last two or three years to make a big piece of cloth from which this dress will be made. I think I’ve finally got enough yarn spun and ready to be put on the looms.

I’ve been experimenting with Viking-style dress patterns, because that was clearly a time when cloth was still prized, and as precious as it actually is. A lot of the patterns weren’t shaped by cutting into the cloth—it was all put together using rectangles of cloth as they came off the loom. That’s really informed the width of the cloth I’m going to weave and how I’m going to construct the dress.

Hopefully that will be woven over winter, and then I can actually turn it into a finished garment. It’s going to be nice to have something physically manifest, that shows me at any rate what’s possible.

AD: It’s very telling that it’s taken one person two or three years to get enough fibre for a dress.

AB: Yeah. It immediately makes me think that for a tribe or a group of people to be wearing this cloth, it would have been a group effort. And because it’s so time consuming, it gives you the feeling that people weren’t just surviving—they were thriving. There was enough give in the community where you could start to invest in creating something, over and above what was strictly necessary for survival.

As far back as there’s objects that exist from the past, there’s always this level of beauty, it’s not just functional. It gives me the feeling that the creative process and this desire to create beautiful objects is as old as we are.

I’m sure, given the fineness and the finesse of these bits of yarn that were found, that people were wearing really amazing outfits made from nettles. They weren’t just rough things tied around themselves. I imagine they were beautiful and functional and astonishing.

This project was undertaken on the lands of the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung peoples, who have never ceded sovereignty. I pay respect to Elders past and present, and particularly acknowledge the Wurundjeri Willam people who have maintained and farmed the Merri Creek area since time immemorial. I honour their deep and living knowledge of its plants, animals and seasonal cycles. As an occupier I strive to live respectfully and in a spirit of collaboration with this place.

Always was, always will be Aboriginal land.

Working with Weeds is an interview series developed during a Blindside ‘Isolation Residency’ in August 2020. As a public outcome of the residency, this interview project is facilitated and supported by Blindside through funding from City of Melbourne.

Text by Anna Dunnill, November 2020